ECUADOR

Marxist-Leninist Communist Party of Ecuador (PCMLE)

Pablo Miranda

The first decade of the 21st century was the scene of the rise, through

elections, of various “progressive governments” in Latin America. These

governments came about under special circumstances, when the struggle

of the masses and youth was recovering from the ebb that occurred in

the 1990s, when the neoliberal policies were worn out and showed their

inability to resolve the crisis, at a time when the prestige of the

bourgeois institutions and the traditional political parties had hit

bottom. These governments emerged with the support of the trade union

and popular movement, of the political organizations and parties of the

left, but they also expressed a realignment of the various sectors of

the ruling classes, including the international monopolies, mainly from

the U.S.

These governments proclaimed their opposition to neoliberalism, to the

Free Trade Agreement with the U.S., to the chains of external debt,

calling for its renegotiation. Internally, they lashed out at those

entrenched in power, at the traditional political parties, at

corruption and selling-out. They proclaimed democracy, change, the

revolution that they gave different names, “citizens”, “Bolivarian”,

“Andean revolution”, “21st century socialism” in opposition to the

revolutionary struggles and governmental experiences of the

revolutionary Marxist-Leninists of the 20th century.

The arrival of these governments coincided with the rise in prices at

the international level of the natural resources, raw materials and

agricultural products produced in appreciable quantities in the various

countries of the subcontinent. During this period the most serious

international economic crisis since the 1930s took place, which began

in the U.S., spread around the world and significantly affected the

dependent countries, mainly in Latin America. However, in Latin America

the consequences of this crisis were overcome relatively quickly,

precisely because of the rise in commodity prices. In many countries of

Latin America, such as Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Brazil, Argentina

and Costa Rica, foreign direct investment, loans and the purchase of

millions of hectares of farmland multiplied. In almost all of the

countries, huge resources are being invested in gold, silver, copper,

lithium and iron mining, as well as in oil exploration and

exploitation. This aggressive penetration of international capital

contributed to the growth of GDP, which appeared as the manifestation

of the generosity of capitalism as a system and of foreign investment,

and, in the case of the “progressive governments”, as an expression of

interdependent development.

These circumstances were common among all the Latin American countries,

regardless of the political orientation of their governments and

expressed in sustained growth rates of an average of 4.5% for roughly a

decade. However, in 2013 this growth fell to 2.7%, and for 2014, the

World Bank estimates that it will fall to 2.2%.

Latin America has always been considered the backyard of the U.S., and

the U.S. government defended that circumstance in the economic,

diplomatic and military field. However, the other imperialist powers of

Europe and Asia, the international monopolies are not ceasing their

policy of capital export for the exploitation of natural resources, for

banking and finance and even for industrialization. In recent years

China has become a power in the export of products of light industry

and one of the largest lenders.

In most countries that macro-economic development was expressed in

large public investment, in modernizing of the economies, in an

aggressive welfare policy directed to the poorest sectors of society,

in the formation of an electoral base of support among the masses.

Most of these “progressive governments” proclaimed a nationalist

discourse, combating neoliberalism and the oligarchies, and they

succeeded in achieving a good deal of popular support at the polls.

Some of them, Venezuela, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Bolivia talked of “21st

century socialism” and presented themselves as an alternative to

revolution and socialism, which they reviled as anti-democratic and

failed.

Despite the nationalist discourse, including anti-U.S. imperialist

discourse, the U.S. monopolies and their governments always understood

that the capitalist system was not at risk; and that due to the

disappearance of the USSR and its area of influence, these progressive

governments had to remain in the sphere of the U.S. monopolies; this

led to tolerance toward these regimes. This tolerance always included

political and economic pressure to completely reintegrate them into

their spheres. In Venezuela they are openly intervening in support of

the reactionary political organizations, of coups, lockouts, street

riots and terrorism.

These “progressive governments,” all representing the interests of a

sector of the bourgeoisie, were able to form a group of countries that

expressed their alignments: ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples

of Our America), and further, at the regional level UNASUR (Union of

South American Nations) and CELAC (Community of Latin American and

Caribbean States); at the same time they are putting pressure on the

OAS.

The popular movement, the unions, teachers, youth, women, indigenous

people and environmentalists who resisted and fought neoliberalism,

which were forged in those battles, in essence to direct their actions

into electoral contests and in all those countries they supported the

alternatives that later became the progressive governments.

These new circumstances of an objective and subjective character

significantly influenced the understanding, consciousness and state of

mind of the working masses and the youth. The bombastic discourse of

the “progressive” chieftains, the intense work of social democracy and

opportunism, the fulfilment of a part of their electoral promises and

the diatribes of reaction and the right in opposition to those

governments affected the behaviour of the organized popular sectors.

They determined the need to support certain changes in the course of

the economy and politics, to push forward the democratic and

nationalist positions towards consistent positions. They agreed to

postpone some of their own demands for the benefit of the general

interest. Some sectors promoted the illusion that those governments and

their projects would be the way to solve the problems of the workers

and the development of the countries. To a large extent these events

were a breeding ground for the development of reformist, pacifist and

opportunist positions that are found in the mass movement.

On the other hand, the emergence of these progressive governments meant

the defeat and breaking up of the traditional parties of the

bourgeoisie, of the reactionary right and of classical social

democracy. However, all the ruling classes understood that these

regimes did not affect their fundamental interests and coexisted with

them to benefit from their policies. In the case of Ecuador, for

example, the chambers of commerce, all the big business owners and

bankers were and are benefiting significantly; they obtained revenue

and profits higher than those achieved during the governments of the

traditional parties. In fact, the various factions of the ruling

classes have not given up challenging the government for succession

through elections. In Venezuela the reactionary sectors and the

oligarchy as well as the U.S. have chosen the path of coups, of

economic destabilization and even the mobilization of the masses for

street fighting.

The existence of these progressive governments has generally led to the

demobilization of the trade union and popular movement. The illusions

in the modernization of the country, in some concessions to the demands

of the masses; the impact of the welfare policies; the configuration,

except for the government of Venezuela, of dissuasive policies

regarding the futility of the trade union and social struggle, of

threats and blackmail and, in countries such as Ecuador, Argentina and

Bolivia the implementation of repressive policies restricting trade

union and social rights, the right to organize and strike, leading to

the criminalization of the social struggle, the persecution and

imprisonment of social fighters have caused a significant level of

demobilization of the popular movement.

On the other hand, the emergence of these progressive governments meant

the defeat and breaking up of the traditional parties of the

bourgeoisie, of the reactionary right and of classical social

democracy. However, all the ruling classes understood that these

regimes did not affect their fundamental interests and coexisted with

them to benefit from their policies.

The developmentalist and reformist policies are reaching their limit

The progressive governments in Latin America have existed an average of

ten years. In this time, everything indicates that they are nearing the

end of their cycle. There are several factors limiting the economic

growth of these countries, including:

- Declining commodity prices.

- The beginning recovery of the economies of the U.S. and of Germany in Western Europe.

- The

slowdown in the economies of the emerging countries, China, India and

signs of recession in Turkey, South Africa and Brazil.

- The

aggressive growth in foreign debt, mainly with China, and the high

interest rates imposed by this new creditor, an average of 6%.

- The

reprimarization of the economy. The great majority of Latin American

countries, including those governed by the “progressive governments/1

are net exporters of raw materials, mineral resources and oil,

agricultural and livestock products. These circumstances are well known

in Brazil and Argentina, countries whose exports are mainly soy, meat,

wheat, iron and copper. The other countries are “specialized” in oil,

gas, aluminum, lithium, bananas, coffee, cocoa, soy and flowers.

- Everything

seems to indicate that a new worldwide recession is approaching that

will significantly affect all the countries in Latin America; that in

this new situation it will not be possible for the price of commodities

to recover. As we know, there are signs of overheating in the economies

of China and India, which will not serve as shock absorbers as happened

in the 2007 crisis.

These circumstances are significantly limiting the tax revenues and

therefore limiting the possibilities of continuing to show the material

and social achievements that can shore up the support from the popular

sectors.

In Venezuela, for example, despite the great production and export of

oil and the huge revenues from these sources, the government has not

been able to solve the provision of foods of basic necessity and the

resources for the daily life of the masses, not even to a moderate

degree. In Brazil, whose macro-development put it in sixth place among

the major economies of the world, great social inequality is evident,

as is the poverty in the countryside and the slums; the aspirations of

tens of millions of young people who have no access to either education

or work, who have no prospects in life, continue to be unfulfilled. In

Ecuador, despite the fact that in the last six years Correa’s

government had income higher than that of the previous governments in

50 years, the problems of poverty, unemployment and underemployment

continue to devastate the great majority of Ecuadorians, with an

unemployment of 5% and underemployment of over 50%, according to

official figures. In Argentina, the surpluses in the trade balance were

transformed into their opposite, into deficits, and the working class

and the laboring masses are seeing their incomes decline and

unemployment growing. In Nicaragua and Bolivia the economic growth

rates are at the lowest level.

In Venezuela, for example, despite the great production and export of

oil and the huge revenues from these sources, the government has not

been able to solve the provision of foods of basic necessity and the

resources for the daily life of the masses, not even to a moderate

degree. In Brazil, whose macro-development put it in sixth place among

the major economies of the world, great social inequality is evident,

as is the poverty in the countryside and the slums; the aspirations of

tens of millions of young people who have no access to either education

or work, who have no prospects in life, continue to be unfulfilled. In

Ecuador, despite the fact that in the last six years Correa’s

government had income higher than that of the previous governments in

50 years, the problems of poverty, unemployment and underemployment

continue to devastate the great majority of Ecuadorians, with an

unemployment of 5% and underemployment of over 50%, according to

official figures. In Argentina, the surpluses in the trade balance were

transformed into their opposite, into deficits, and the working class

and the laboring masses are seeing their incomes decline and

unemployment growing. In Nicaragua and Bolivia the economic growth

rates are at the lowest level.

Post neoliberalism will not overcome the evils of capitalism

It is clear that in Latin America, in essence, the policies and

achievements of neoliberalism are exhausted and are essentially

superseded. The question is, what policies are replacing neoliberalism?

Essentially, neoliberalism failed in its intention of overcoming the

general crisis of capitalism, and more specifically the crisis of

international finance capital. The essence of neoliberalism was thrown

overboard due to the resistance and struggle of the working class and

peoples; but also successive readjustments within the monopolies

affected their intention, in their dispute over the appropriation and

concentration of wealth, and among the various sectors of the ruling

classes in each country. To face the international crisis of 2007 they

aggressively utilized public monies, and indeed the role of the states

was again decisive. The monopolies acted in their own defence through

public policies both in the imperialist countries as well as in the

dependent countries. However, labour flexibility and freedom of trade

for the monopolies basically continue in force.

As we have noted, in Latin America, the emergence of the “progressive

governments” set neoliberalism as their principal target, it expressed

the discontent of the working masses and the youth and put forward some

new policies. In the name of change they readjusted the pieces so as

not to affect the system; the ruling classes, the big business owners

and bankers preserved their interests and increased them, utilizing a

smokescreen of investing significant amounts of tax money to promote

public works, wage concessions and aggressive welfare policies. In the

name of sovereignty and independent development, they renegotiated

dependency with the U.S. and the European Union; China with its booming

economy aggressively entered into that “re-engineered” global economy

for its own interests.

In the final analysis, in most Latin American countries, but especially

in those where there exist “progressive governments,” the policies of

neoliberalism are being superseded, which does not mean entirely

cancelled. In their place one can see a modernization of the economies,

which goes hand in hand with important tax revenue. Public works are

especially visible: highways, ports, airports, hydroelectric plants,

hospitals and schools. In no country in Latin America have the

interests of the monopolies and the oligarchy been affected; in no

state have social reforms that were begun been consistently completed.

In all the countries the process of capitalist accumulation comes from

the exploitation of the working class and the other labouring classes.

In the case of the “progressive governments,” these post-neoliberal

policies led to demobilizing the workers and popular movement, sowing

illusions, dividing the trade union movement and in some cases trying

to corporatize workers hand in hand with government action.

The popular movement in the new scenario

The awe of the masses regarding the democratic and patriotic character

of the progressive governments in Latin America is fading. This is

mainly because the essential problems of the masses have not been

resolved, because the dependency of the countries of Latin America

remains a reality.

The awe of the masses regarding the democratic and patriotic character

of the progressive governments in Latin America is fading. This is

mainly because the essential problems of the masses have not been

resolved, because the dependency of the countries of Latin America

remains a reality.

Important events are taking place:

- The disenchantment of the popular masses and the youth

regarding the solution of their basic problems and the illusions

created by the material progress and development of the country.

- The

unmasking of the developmentalist and reformist character of these

“progressive governments” in most of the organized trade union and

popular movement and among important sectors of the youth.

- In

Ecuador much of the indigenous movement is involved in the struggle

against the repressive and anti-democratic character of Correa’s

government. In Bolivia, despite the multinational proclamations an

important sector of the indigenous peoples are distancing themselves

from the Morales government and are calling for their own rights.

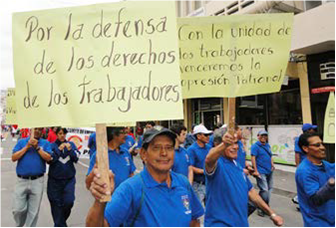

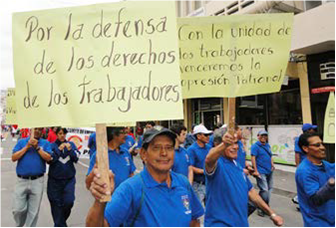

- Demonstrations

of discontent and dissatisfaction with the economic and social

situation of sectors of the workers and mainly of the youth that are

seen in marches, strikes and demonstrations to demand their rights. The

march for water in Ecuador, the strike of teachers in Argentina, the

mobilizations of the working class in Bolivia are part of these

demonstrations.

- The mobilizations of the youths in

2013 that shook the streets of the major Brazilian cities are the

highest expressions of the social and political struggle, with

important ideological anti-system expressions. They are laying bare the

achievements of the Workers Party government, showing them as serving

capitalism and the big oligarchy and very far from satisfying the

material and spiritual needs of the masses and particularly the youth.

- In other countries, those where the right-wing governments rule,

the struggle of the working class, the peasantry and the youth for

their rights, of the communities opposed to large-scale mining and for

the protection of the environment, continue to develop in important

degrees: the miners in Colombia, the workers in Mexico, the students in

Chile, the communities in Peru, the peasants, teachers and students in

Honduras

- Among

the various organizations calling themselves left-wing, among the

revolutionary parties and organizations, positions are being demarcated

between reformist illusions and social change, between 21st century

socialism and Marxist positions, between revisionism and

Marxism-Leninism. The old revisionist parties joined up with the

“progressive” capriciousness and are obsequiously on the side of the

“progressive governments”; in the same camp are other political

organizations of the petty bourgeoisie, as well as renegades from

revolutionary positions. In the trenches of social change, of the

revolution, on the side of the workers and peoples, in defence of their

interests and rights, in the struggle to overcome capitalism are many

of the organizations that defined themselves as left-wing in the past,

new organizations that emerged in the class confrontation with the

bourgeoisie and imperialism and, consistently, the Marxist-Leninist

parties and organizations.

- The armed revolutionary

struggle which took unequal forms in various countries of Latin America

in the 20th century, which achieved victory in Cuba and Nicaragua and

was defeated militarily in other countries, continues to be active in

Colombia. This year the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia)

will mark the 50th anniversary of the start of the battles for the

seizure of power; other forces such as the EPL (People’s Liberation

Army) and the ELN (Army of National Liberation) are also persisting in

the legitimate use of revolutionary violence.

- The

theoretical and political debate between the left and the right,

between revolution and reform, between Marxism-Leninism and revisionism

is put forward and developed in all fields. That result will take place

in theory and in practice.

There is the prospect of a new rise in the revolutionary struggle

The analysis of the economic and social situation, of the relationship

of forces in the confrontation between workers and bosses, between the

peoples and the oligarchy; of the contention between different factions

of the monopolies and the imperialist countries; as well as the

contradictions within the bourgeoisie in each country, allows us to

foresee important political events in the near future.

- The working masses are facing in a determined manner

the struggle for their wage demands and for stability, for the

reconquest of their labour rights, and they are advancing in

recognizing and acting as protagonists of change, for the revolution

and socialism.

- The peasants are continuing their

struggles for the defence of the water, for the land, in opposition to

the Free Trade Agreement with the U.S. and European Union, against the

large-scale open-pit mining.

- The teachers are developing the struggle for a civic education and for labour rights to new levels.

- The

youth are joining the large mobilizations in massive numbers in defence

of human rights, of the environment and nature, in defence of national

sovereignty, democracy and freedom.

- The indigenous peoples are playing a leading role for national rights and are joining the struggle for social liberation.

- The

theoretical political debate between the left and right, between

reformism and the revolution, will intensify and the revolutionary,

Marxist-Leninist positions will be affirmed in the consciousness and

organization of the working masses and the youth.

The course of history cannot be held back. Capitalism is trapped in

its insoluble contradictions, in the inter-imperialist confrontations

and is besieged by the workers and peoples, and in Latin America great

class combats will take place.

Pablo Miranda

Ecuador, March 2014

Click here to return to the Index, U&S 28

In Venezuela, for example, despite the great production and export of

oil and the huge revenues from these sources, the government has not

been able to solve the provision of foods of basic necessity and the

resources for the daily life of the masses, not even to a moderate

degree. In Brazil, whose macro-development put it in sixth place among

the major economies of the world, great social inequality is evident,

as is the poverty in the countryside and the slums; the aspirations of

tens of millions of young people who have no access to either education

or work, who have no prospects in life, continue to be unfulfilled. In

Ecuador, despite the fact that in the last six years Correa’s

government had income higher than that of the previous governments in

50 years, the problems of poverty, unemployment and underemployment

continue to devastate the great majority of Ecuadorians, with an

unemployment of 5% and underemployment of over 50%, according to

official figures. In Argentina, the surpluses in the trade balance were

transformed into their opposite, into deficits, and the working class

and the laboring masses are seeing their incomes decline and

unemployment growing. In Nicaragua and Bolivia the economic growth

rates are at the lowest level.

In Venezuela, for example, despite the great production and export of

oil and the huge revenues from these sources, the government has not

been able to solve the provision of foods of basic necessity and the

resources for the daily life of the masses, not even to a moderate

degree. In Brazil, whose macro-development put it in sixth place among

the major economies of the world, great social inequality is evident,

as is the poverty in the countryside and the slums; the aspirations of

tens of millions of young people who have no access to either education

or work, who have no prospects in life, continue to be unfulfilled. In

Ecuador, despite the fact that in the last six years Correa’s

government had income higher than that of the previous governments in

50 years, the problems of poverty, unemployment and underemployment

continue to devastate the great majority of Ecuadorians, with an

unemployment of 5% and underemployment of over 50%, according to

official figures. In Argentina, the surpluses in the trade balance were

transformed into their opposite, into deficits, and the working class

and the laboring masses are seeing their incomes decline and

unemployment growing. In Nicaragua and Bolivia the economic growth

rates are at the lowest level. The awe of the masses regarding the democratic and patriotic character

of the progressive governments in Latin America is fading. This is

mainly because the essential problems of the masses have not been

resolved, because the dependency of the countries of Latin America

remains a reality.

The awe of the masses regarding the democratic and patriotic character

of the progressive governments in Latin America is fading. This is

mainly because the essential problems of the masses have not been

resolved, because the dependency of the countries of Latin America

remains a reality.