more evidence of revisionist treason

In the 1960s, the break with Khrushchev-ism was the origin of the formation of the first Marxist-Leninist parties. This phase of the international communist and workers movement is yet to be written. The Marxist-Leninist movement had several phases; the first was the break with the revisionism in the CPSU and the international communist movement. The second phase, in the context of the Cultural Revolution in China, was marked by the influence of Maoism within the new parties. The third was the ideological break with the theory of the “three worlds,” which is the origin of the specific ideological and militant ties which unite the Marxist-Leninist parties today.

In this contribution I will limit myself to the first phase and, except for some references, essentially to the break of the European parties with revisionism.1

Differences kept secret

The differences within the communist movement regarding the Khrushchevite revisionist policy of peaceful coexistence with imperialism and about the underestimation of the historical significance of the revolutions in the Third World (Africa, Asia and Latin America) for a long time were known only by the leaders of the communist parties. In the joint Declaration of the Communist Parties of 1957, one can read that “bourgeois influence is an internal cause of revisionism, while surrender to imperialist pressure is its external source.” But only in 1960 did the differences between parties and States come to light.

In the months preceding the Conference of the Communist Parties in Moscow,2 the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced their positions, specifically in an editorial in Honqqi Long Live Leninism.3 The critique of Khrushchevite revisionism centred primarily on the question of war and peace, on peaceful coexistence, on the paths of transition to socialism and on Stalin and Yugoslavia. The publication of Long Live Leninism and other documents resulted in harsh debates in the General Council of the World Federation of Trade Unions in June of 1960, and later in the Congress of the Romanian Communist Party. In that Congress the CCP denounced the revelation that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) had sent a confidential letter to the CC of the CCP, which it called a “program of an anti-Chinese campaign.” The parties of East Asia and Latin America that supported the positions of the CCP were instructed to criticize themselves; in Europe the alignment of the leaderships of the communist parties with the positions of the CPSU was general.

|

| The romance between Khrushchev and Kennedy, more evidence of revisionist treason |

At the Conference of the communist parties in Moscow, the CPSU launched a general attack against the parties that opposed their line, accusing them of “deviationism” and “anti-Sovietism.” The pressures were particularly strong against the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA), demanding that it decide whether Albania “would unite with the 200 million (population of the USSR) or the 650 million (population of China).” It is an argument that showed the conception of the relations between parties that predominated in the leadership of the CPSU. The delegation of the PLA headed by Enver Hoxha refused to submit to such pressure, and as a result he was attacked and slandered at the Conference by all parties that had aligned themselves with the CPSU; however, he did not yield on the principles he defended.

The final declaration of the Conference was a compromise that nevertheless hinted at the differences. The document was along the line of “peaceful coexistence” and “peaceful transition to socialism” of the CPSU, but it also noted the importance of the historical phase of decolonization and that “the world revolutionary cause depends on the revolutionary struggle of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America, where the great majority of the world’s population lives.”

The differences between the parties also concerned the relations between States; thus the USSR put economic pressure on China and Albania, withdrawing its technical specialists from those countries. After the Conference, the pressures were concentrated against Albania, despite what Khrushchev had said during a visit to Tirana. “Don’t worry about bread. In the USSR, the rats eat as much wheat as you consume!” However, in the critical situation in which Albania did not have more than a 15 day of wheat reserves and faced the danger of famine, it had to wait 45 days for Moscow to send 10,000 tons of wheat instead of the 50,000 promised.

In addition to these hostile measures, the PLA was not invited to the 22nd Congress of the CPSU; Khrushchev, Pospelov, Kuusinen, Suslov and Brezhnev, supported by the “parrot parties,” multiplied their criticism of the PLA. From then on, to defend or attack Albania was the line of demarcation between Marxist-Leninists and revisionists. The CCP declared that “the open, one-sided condemnation of a fraternal party does not favour unity.... It cannot be considered a serious Marxist-Leninist attitude to expose the discussions taking place between fraternal parties and countries before the enemy “. The PLA did not yield to these pressures, and on December 6, 1961, the Soviet Union broke diplomatic relations with Albania, supported by all the countries aligned with the USSR. Albania was then subjected to a double economic blockade, from COMECON in the East and from the capitalist camp in the West.

From that time on, opposition to Khrushchevite revisionism had a base in Europe. At first, it was in Asia where the Indonesian Communist Party, the most important party in the world that was not in power, opposed the line of the CPSU. In Latin America, in February of 1962, the leaders expelled from the Brazilian revisionist party formed the Communist Party of Brazil, the first Marxist-Leninist party that was formed and was the most advanced in the fight against revisionism.

The first Marxist-Leninist parties in Europe

The break with revisionism came at a time of heated discussion about the revolutionary ideas that were confronting colonialism and dictatorships around the world. That confrontation was fierce in Western Europe except in Portugal and Spain, with dictatorships in power and where the class struggle was not as intense as in the other continents, in particular what has been called the “glorious thirty.” The most reactionary forces had not raised their head after the defeat of fascism. The conservative and social-democratic powers, under great pressure from the aspiration of the masses for socialism, agreed to apply a Keynesian social policy that would allow the exploitation of the South by the North, deceiving broad sectors of the public about the true nature of capitalism.

If the polemic was made public, both in France and Italy, countries with the most important communist parties, in the underground party in Spain, and also in other European parties, the members did not have any more information than the speeches and documents of the leaders, who defended the position of the CPSU. In 1962 the revisionist parties decided to remove the articles and documents of the CCP and the writings of Mao Zedong from communist bookshops, thus preventing the members from knowing those documents. It was unacceptable silence for communist parties to try to impose on a fraternal party. How could one judge without knowing the positions of one party, without knowledge of those of the other side?

To address this scandalous boycott, initiatives arose to publish and distribute the articles of the Chinese and Albanian parties and to make their positions known; a powerful information network was organized specifically with the publication of the journal Peking Review in many languages, which until then was only published in English.4

In addition to the Soviet party, the French Communist Party (PCF) and Maurice Thorez in particular were the ones bent on defending the revisionist line of Khrushchev and the “Italian road to socialism”, represented by the Italian Communist Party (PCI) of Palmiro Togliatti, which put forward the main criticisms against the Marxist-Leninists, the first Thorez for his tailism, the second Togliatti, for the ultra-revisionist line that he advocated.

Two theses of the 10th Congress of the CPI, in December 1962, have a particular significance today. The first: “We must demand... that a systematic action be developed to overcome the division of Europe and of the world into blocs, doing away with political and military obstacles that maintain this division... in order to reconstruct the single world market.” As history has gone that route, the contemporary effects of globalization and of a “single world market” evidently condemn the theses of the PCI and Togliatti. Another incorrect PCI thesis: the ruling groups of the bourgeoisie may now accept “the concepts of planning and economic programming that for some time have been considered a socialist prerogative... this is a sign of maturity of the objective conditions for the transition from capitalism to socialism.”5 This concept was announced at the time when the theses of Friedrich Hayek6 were becoming the basis of neoliberal politicians and economists.

The deepening of the ideological struggle

|

|

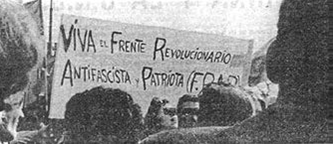

[Sign reads: Long Live the Anti-Fascist and

Patriotic Revolutionary Front (F.R.A.P.)] Tactic put forward by the Communist Party of Spain (Marxist-Leninist) in the 1960s and ‘70s |

The CCP and the PLA published numerous documents denouncing “modern revisionism” ideologically and with facts, by analogy with the revisionism of the 1890s.

An essential article that systematized this criticism was the “Proposal Concerning General Line of the International Communist Movement,” known as “The Twenty-Five Points,” published by the CC of the CCP on June 14, 1963. The fight against Khrushchevism was growing, based on these documents and registered its criticism in the Lines of the Parties: in 1963 and 1964, communist parties and organizations were founded in Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Ceylon, Thailand, New Zealand, Canada, etc.

An essential fact in this ideological and political struggle (beyond the fact that the communist parties that criticized the revisionist line were led by two parties in power) is that this criticism arose from within the communist movement. That gave the right to think and act without splitting, but belonging to the international communist movement, and if the revisionist parties could exclude the Marxist-Leninist militants, they could not condemn them to ostracism; they could not deny that they were part of the movement.

In Belgium, Spain and Switzerland, the first communist parties and organizations were formed in Europe. This process took different forms in each country depending on the level of the class struggle, the influence of the ideas of socialism, the history and traditions of the workers’ movement, the intensity of the repression of the state apparatus and the ability of the Marxist-Leninist comrades. Within the European parties the struggle was essentially carried out by mid-level cadres and grassroots members. An exception was the Belgian Party, in which the struggle between the two lines led to a vertical split from the base to the Central Committee: Jacques Grippa, having been removed, reconstructed the Communist Party of Belgium (PCB) with cadres forged in the antifascist struggle of the 1930s, such as Henri Glineur and Jules Vanderlinden. The PCB played an important role of coordination among the new organizations in this initial phase.

Raising the banner of denunciation of the revisionist danger, Elena Odena and other comrades who formed the Communist Party of Spain (M-L) launched with determination the fight within the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) against the line of Santiago Carrillo, under the difficult conditions of clandestinity in Spain and in political exile.

In Switzerland, the regrouping of the Marxist-Leninists took a particular turn: a political adventurer there created a Swiss communist party; it was necessary to know and expose his role as a provocateur, especially when the international press used him to create confusion with his statements.

He was unmasked very quickly and this attempt to infiltrate the young Marxist-Leninist movement failed.7 Because of this, the Organization of Swiss Communists (OSC) was created to respond to this provocation, but without doing the ideological and political work necessary for the constitution of a party.8

In many parties, once the fight was launched, a stage of clarification was necessary to define the Marxist-Leninist line, to seek ideological and political unity among its members, to overcome egotism and to resist the pressures of the capitalist power and the revisionist parties. It was a tough fight, because for many members of the revisionist parties, the USSR was the homeland of socialism, which had played a decisive role in the victory over Nazism; they were loyal to and identified with the Bolshevik revolution and with their aspiration for another world. These are feelings that cannot be ignored.

In 1965 other Marxist-Leninist organizations were founded in Austria, Germany, France and Poland; internationalist ties were created among the new parties and organizations. The meetings and exchanges with the CCP and the PLA were privileged sources to know and understand the intensity and commitment of the international class struggle and the socialist transformation of society in conditions of the unequal relationship of forces with the capitalist world due to the Khrushchevite deviation. The new parties, even the weakest, were not locked into a small-group ghetto.

Towards an international Marxist-Leninist movement

At the beginning the relation of forces between the two lines, internationally, was ambiguous and its development was unpredictable. Within numerous parties that were faithful to the CPSU, there existed, even in the leadership, doubts about how the debate within the communist movement would develop. This was especially true in October 1964, when Khrushchev was removed from the leadership of the CPSU as a result of a struggle for power, of course, but also and above all, for the denunciation of his policy (the conditions of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty with the U.S., the unilateral withdrawal of missiles from Cuba, ambiguities in the defence of the struggle of the Vietnamese people against imperialist aggression) to gain influence and force the CPSU to stop believing that it rejected “Khrushchevite revisionism.”

Nikita Khrushchev become a discredited spokesperson, his removal temporarily eased the polemics, while the position of the new Soviet leaders was being judged; but once it became clear that Kosygin and those that succeeded him were following the same policy, the split was final.

An important demonstration of the reality of the Marxist-Leninist movement was the celebration of the 5th Congress of the PLA in November 1966, which was attended by the CP of China and 28 Marxist-Leninist parties and organizations from the five continents.9 There was great enthusiasm, for Albania it was one of the great moments in its history, it had defeated the revisionist and imperialist blockade; for new parties it was the first time they had been able to get together in such great numbers.10 One important note was the recognition of the new parties and the role that tailism and creeping adulation could play in that recognition. Due to lack of vigilance, the Dutch organization, the creature of the CIA, was invited. But one of the first and major ML parties in Europe, the Communist Party of Spain (M-L), was not invited! That mistake was quickly overcome due to the firmness of the line defended by Elena Odena and Raul Marco within the Marxist-Leninist movement; however that was a grave error of political and ideological appreciation.

When the 5th Congress of the PLA was held, in China the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution had been launched several months previously: a “Cultural Revolution group of the Central Committee” and the first Red Guard organizations had been established. The content of the Cultural Revolution is still poorly understood, but its goal – the revolution within the revolution against the influence of bourgeois ideology and the bureaucratization of the Party and State – a lesson learned from the experience of the revisionist parties, appeared to be a necessary historical stage for the Marxist-Leninist parties.

The 5th Congress of the PLA was a great moment of affirmation of the Marxist-Leninist movement and an essential discussion was held at bilateral meetings about what structures to develop or not for the Marxist-Leninist movement. That was a request and aspiration of the majority of the new parties present at that congress; Enver Hoxha and the PLA were rather favourable. If no one proposed the formation of a new “International” it was not because the conditions were not ready, the need for an organization or a form of relationship among the Marxist-Leninist parties was felt necessary to strengthen the ties and unity, as well as to learn from the experience of each party. The problem was openly raised conscientiously and seriously. The response of the CCP delegation was negative, under the pretext in particular of shortcomings of the movement, it was better to limit oneself to bilateral meetings, sidestepping in particular the multilateral meetings that would allow exchanges and open the field of the ideological and political experience of each party and have an informed opinion on the positions that could be taken by one or more parties. The rejection was lamented by many of the parties and was judged as a lack of confidence, or remoteness, of the CPC with the Marxist-Leninist movement.

With the deepening of the Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Marxist-Leninist character and composition of the movement was changed, giving way to a new phase, commonly called Maoism.

Thus, from its origins, in its militant and revolutionary work, the Marxist-Leninist movement has been confronted with issues raised. Despite the political situations, which were often difficult, despite the unfavourable balance of forces and despite the attacks and repression suffered, the movement showed its capacity to respond, and fifty years later, the magazine “Unity and Struggle” gives testimony that no force has been able to liquidate it.