On Poetry

Nazim Hikmet

Sectarianism in art is our greatest enemy, especially in the question of form. Those who exclude poetry in rhyme and measure are as narrow-minded as those who believe that there can be no poetry without rhyme and measure. Poetry can be written both ways… I wasn’t less sectarian when I was young. After writing poetry in classical folk measure and rhyme, I sought for novelty in form and began to write in my own way, in a kind of free measure. At its roots was the folk measures of poetry, and even aruz (prosody written according to the rules of classical Turkish poetry, Translator’s note.) sometimes. It was the same for rhyme and language. But I attempted to suggest that this was the only way for writing poetry. I didn’t write any love poems for a long time. I didn’t even use the word ‘heart’ in my poetry, because it was the symbol of feelings, not of the mind. There were times when I was after the most colourful and harmonious poems. I thought that it would be more enjoyable, better understood and more effective if I said what I wanted to say to the people in that way. There were also times when I wanted to present my song in its most basic and invisible form. When was I mistaken? In my opinion, we need both ways and many others. An artist has to search for the most suitable forms non-stop, until the end of his life, in order to have his songs listened to by the people. Sometimes these efforts do not produce anything but months’ long headaches and suffering. Never mind that. Sometimes he is mistaken. Let it be. An artist who doesn’t suffer from headaches, nervous-breakdown, who is not mistaken, would not advance.

Now I use all forms. I write in both folk measure and in rhyme. I also write poetry in the simplest possible form, in everyday language, without a measure or rhyme. I write about love, peace, revolution, life, death, joy, sorrow, hope and desperation; I want my poetry to cover everything human. I want my reader to find the expression of all their feelings in my, or our, poetry. Let them read our poetry when they want something for May Day, or something for their platonic love.

A poet talking about himself or not, talking to one person or to the millions… This doesn’t explain anything about his philosophical or political views. There are poets who don’t talk about themselves but talk to millions, but who are also the representatives of mystic, subjective, idealist, or even religious philosophy. On the other hand, there are many poets who talk about only themselves, but who are materialist, even dialectical materialist. And their poems have been embraced by the masses.

I want to write poems which talk about myself, poems which talk to a single person and to millions. I want to write poems which talk about an apple, about the upturned soil, about the psychology of someone returning from a dungeon, about the fight of the masses for a better future, about the sorrows of love. I want to write poems both on fear of death and on fearlessness towards death.

Since I became a poet what I have been expecting from art is that it should serve people and call them for a better future. That it should be the voice for people’s suffering, their anger, hope, joy and longing. This is what has not changed in my understanding of art. The rest of it has changed, is changing and will change constantly in order to be able to express the unchanged in the most touching, talented, useful, beautiful and perfect way.

(Nazim Hikmet talking about his understanding of art, compiled by Ekber Babayev, 14/11/1965, based on Hikmet’s own writings and his dictations to Babayev.)

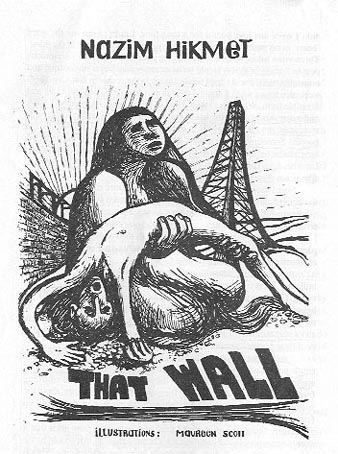

Illustrator’s Note

That Wall is a poem depicting the mass terror and widespread horror thrown up by capitalism-imperialism in the era of its senility. It is a poem showing one side of class struggle – the side which arouses the greatest feeling of revulsion and loathing, and which many well-intentioned people, particularly the type of liberal intellectual which forms the main prop of the revisionist parties, cannot accept. It does not lay emphasis on the strength, the creativity, the resource and unbounded resilience and reserves of the working masses who have the power to rise and destroy this ultimate product of man’s class-divided prehistory, and in this respect may be considered a pessimistic poem. I have nevertheless felt that, in an age when renegade ‘socialists’ seek to cover up the true face of capitalism, representing its ruling monopolist oligarchy as ‘striving for peace’, ‘more reasonable’, ‘interested in the preservation of mankind’, etc., the true face of brutality revealed to tens of millions of struggling peoples in all the continents of the world should find expression in images striving to portray the essence of capitalism-imperialism, and thereby helping to educate all those temporarily taken in by the illusion of relative class peace to a true stance of proletarian internationalism. For so long as exploitation, oppression and war should continue in any corner of the globe, it is necessary to strip away the false mask which the objective allies of imperialism give it, to make it stand exposed in all its diseased violence and inhumanity, so that working people the world over may unite the quicker in the titanic struggle to topple the ‘colossus with feet of clay’, and to usher in the era of socialism and communism. This aim, in my view, Nazim Hikmet fulfils in a powerful and convincing way in this poem.

Maureen Scott

1973

Click here to return to the September 2002 index.