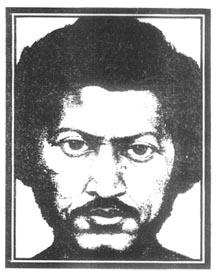

Adieu Comrade !

|

In the sudden death of the painter Anil Karanjai on March 18 this year at Dehradun, Indian art has lost one of its most skilled creative talents. He was sixty and just about a year ago, had decided to divide his time between Delhi and Dehradun where he had set up a new home and studio in a quiet village of the Doon valley. Last year when we visited his new abode in the valley, he was in the best of his elements, eyes gleaming with hope and determination. We were a group of Hindi poets with a couple of local friends. He greeted us with his familiar charm and comradely warmth and without losing time in sweet nothings, he immersed us in a discourse on the painful segregation of different art forms from each other in the contemporary Indian milieu. Anil with his art critic Irish wife, Juliet Reynolds, adopted disabled son Neema and nearly half a dozen dogs (each one picked up from the streets of Delhi in an abandoned or sick state and made a member of his frugal household) had just moved into his new place. He showed us around. This new studio was a huge hall-like room on the first floor of the house – breezy and full of natural light from all sides. For him it was a dream come true, a complete contrast to his cramped studio space in his rented Barsati accommodation at Jor Bagh in Delhi. The surrounding Lichi orchards, hills and the population of voiceless Dalits in his part of the village were an ideal setting for his Marxist self. In that meeting and later on in Delhi he never failed to talk to me of his grandiose creative plans. His last solo exhibition in the LTG Gallery in November 2000 had many a remarkable landscape that also depicted some of the rich visuals from the valley.

Anil Karanjai belonged to a Bengali family of Varanasi that had moved from Rangpur, East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to this holy city of the Hindus during the tumultuous partition of India in 1947. As a child refugee Anil witnessed the most horrific spectacles that the communal hatred had perpetrated in the sub-continent in that year of freedom from the British colonial yoke. There was violence, bloodshed and death everywhere. Amid every moment’s lurking dangers, Anil’s family somehow managed to arrive in India, but the bloodstained memories remained indelibly etched in Anil’s mind.

At a young age Anil showed aplenty the promise of a budding artist. Drawing and sculpting were his natural passions, though he was never sent for a formally structured art training (which his family could ill afford) he became a disciple of a fine local Artist Karnman Singh and learnt a lot from him. Another local artist Ambika Prasad Dubey, too, compassionately taught Anil the use of water colours. Anil always recalls his gurus’ profundity, depth of aesthetic understanding, rare skills and the gentleness for which he felt eternally indebted.

After his semi-formal training in Varanasi, Anil took up the job of an art instructor at nearby Chunar where he experimented in painting and sculpture with his young pupils. It was not a long stint, and it was the only time when he had a salaried job. He got back to Varanasi where, with some fellow artists (Subir, Bibhuti, Karunanidhan, and Bibhas etc.) formed a group called ‘United Artists’. In the turbulent and eventful sixties this group became well known for its anti-establishment role – a veritable extension of the ‘Hungry Generation’ movement of Bengal’s cultural avant-garde.

I had first met Anil and his fellow artists at this juncture in 1966 in a smoke-filled, dimly-lit restaurant at Godaulia in Varanasi. This haunt was frequented not only by the members of the ‘United Artists’ but also by poet Allen Ginsberg, his friend Peter Orlowsky and lots of Indian writers and poets – veterans and the budding ones alike. Apart from their shocking deeds in Varanasi, the ‘United Artists’ shot into fame because of one of their exhibitions in Kathmandu which received tremendous media coverage internationally.

In 1967 Anil visited Delhi to participate in a group exhibition with fellow artists from Varanasi and finally moved to Delhi in 1969. Within a relatively short span of 4-5 years he could carve a niche for himself as a capable painter and Marxist-Leninist activist in the realm of culture. In the beginning of the seventies Anil won the prestigious national award of Lalit Kala Akademi which gave him a well deserved boost – both socially and financially. It was in this period that he met his first wife – Lola – a US national with whom he lived for more than ten years in Delhi and also in the US. In the States he exhibited his works in group and solo shows. Yet, eventually he chose to come back to Delhi as his strong anti-imperialist stance and apathy to the American way of life never allowed him to be at peace with himself. His relationship with Lola also broke.

Back in Delhi Anil resurrected his original self without much effort. His deep involvement with cultural-intellectual ‘actions’ of the left, once again, was noticed with a certain sense of surprise by many who thought that as a natural result of his years of stay in the States, he would join the elite circles and rich connoisseurs. It was never to happen. Instead, they saw him organising group shows in the market places, on the pavements, participating in the protest marches and associating himself with the publication of revolutionary magazines and posters by making drawings and layout designs for them.

His friendship with Juliet Reynolds began in this period which became a lifelong comradeship and remained a perpetual inspiration for his committed non-conformist life style. He had firm and huge moral courage with which he punctured the inflated hollowness of the pretentious glory of those who could make or destroy an artist’s career – the dons of India’s art world. These dons recognised his extraordinary talents, but mostly in a private undefined manner. Anil’s uneasy relationship with this class emanated from his acute understanding of power which he loathed.

Unlike others, Anil Karanjai’s total lack of interest in cultivating favour or ingratiating himself with moneybags did certainly contribute to the serious and shameful underestimation of him as a painter of great qualities.

His early paintings were done in a surrealist mode – sometimes imbued with a dreamlike lyricism but mostly depicting torturous realties through intertwined figures in a torsional weaving. His tough and clear understanding of the victimisation of the weak by the strong all through human history got powerfully expressed not only in the works of the first phase but also later when he painted fossilised and stilled faces in the stones of old ruins and historical monuments. These faces are often writhing in pain as if showing how the common people and their labour are buried in the creation of the grandeur that the rulers take pride in. He also painted portraits that bared the souls of individuals in a stark unromantic manner. In his last phase he was almost obsessed with landscapes. His landscapes are in all sizes – from huge canvasses in oil colours to miniatures in pastel. Aptly, one of his exhibitions was titled ‘Images of Silence,’ where the apparent absence of human figures was mystifying for some of his political friends. But for Anil, the landscapes were a profound quest for beauty, where a reservoir of joyous aesthetic experiences was rediscovered to evoke a world of meaning which is being gradually ignored and lost. In fact, Anil was as deeply sensitive to beauty as to life’s pain and cruelties. Underneath his depiction and rediscovery of beauty there was always a painter with a social conscience who hated the fast increasing ugliness arising from the overall process of inhuman desensitization and stench of injustice. In his own words ‘the artist is the conscience-keeper of society' – the visionary sorcerer whose responsibility it is to exorcise evil by whatever means is available to his knowledge and wisdom. In the same statement Anil also says ‘Art never brings revolution but a true artist, being a conscientiousness person must always side with the forces of change’.

I remain confident that Anil Karanjai would be discovered and appreciated in a big way one day and the art world and generation after generation of aspiring artists would realise that in Anil they had one of the peaks by which they could orient themselves.

For now, adieu comrade!

Pankaj Singh

Click here to return to the September 2001 index.