1939-2018

Rafael Martinez

On April 2nd 2018 Winnie Madikizela-Mandela passed away, leaving South Africa in shock and consternation. Dubbed the Mother of the Nation, Winnie was given a state funeral. Even some who betrayed her struggle and sidelined her politically in crucial times for South Africa did not hesitate to vindicate her following her passing.

Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela was born in the Transkei, in what is now the Eastern Cape, September 26th 1939. Her parents both were English-speaking teachers who were mission-educated. She grew up before the Bantu system of education was established by the apartheid regime. As a result, she had access to education that many after her were deprived of. Winnie graduated from Shawbury High School, where she was educated by graduates of Fort Hare University,1 a well-known enclave of black political activism. In 1953 she was admitted to the Jan Hofmeyr School of Social Work in Johannesburg. She completed her degree in social work in 1955, top of her class. She accepted a position of medical social worker at Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg, the first black person to be hired in that capacity.

She displayed political consciousness early on and before marrying Nelson Mandela. As a social worker, Winnie was politically active and was sensitive to the injustices on blacks by white minority rule. For instance, Winnie performed research in Alexandra Township regarding infant mortality. She concluded that infant mortality decimated 1 in 100 children. She stated at the time that “I started to realise the abject poverty under which most people were forced to live, the appalling conditions created by the inequalities of the system”.

Winnie and Nelson were married in June 1958 while proceedings of the Treason Trial were still in progress. The years of marriage before Nelson Mandela was imprisoned in Robben Island, were such that they would barely spend time together. Nelson Mandela would be either in jail or away on political assignments. In Winnie’s words, Nelson Mandela never discussed politics with her. Winnie becomes a political leader in her own rights under the auspices of the African National Congress and the Women’s League. As she put it, the Women’s League dealt with the “bread and butter” of the struggle and so she got involved to the point of becoming an icon by her own ability. Winnie’s uncompromising, unwavering and tireless struggle played a significant role in turning Nelson Mandela into an icon of the anti-apartheid movement both nationally and internationally.

Winnie was cognizant of the consequences of marrying one of the prominent leaders of the struggle against white domination. Their house was subject to regular police raids. Harassment and intimidation became a way of life for Winnie and it only got worse over the years. In the late 50s her political activism was on the rise. In October 1958 Winnie participated in protest actions against the disgraceful pass laws. Pass laws were tantamount to an internal passport system aimed at effecting segregation, where black labourers would be forced to live in designated areas away from their families. These contrived regulations had devastating effects on the family life of black communities. Pass laws were enforced long before the establishment of the apartheid and used to apply to black men. It was during the apartheid that pass laws were also enforced on black women.

Sharpeville’s massacre in March 1960 became a watershed, a turning point in the struggle against white supremacy. The ANC and other political organizations were banned. After being acquitted in 1961 at the Treason Trial, Nelson Mandela went underground. It is at that time and as a result of the continued violence against black protesters that Nelson Mandela challenges the suitability of peaceful non-resistance. It is at this time that what is to become the armed wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) or the “spear of the nation”, is established. Nelson Mandela was deemed a terrorist by the forces of reaction both nationally and internationally. This was aggravated by the suspicion that Mandela collaborated with communist activists, although he always denied ever being a member of the Communist Party. Following his arrest in August 1962 and his conviction in June 1964, he was imprisoned, including periods of solitary confinement, till his release in February 1990.

Winnie’s political activism intensified with Nelson’s incarceration. As her uncompromising struggle against the apartheid escalated so did the pressure and the cruelty displayed by the police and its ruthless special branch. Her house in Soweto was raided regularly, terrorizing her and her two daughters. This was done with the intent to demoralize and to deter her from political activism. Scores of men would torment Winnie by attacking her house in the middle of the night. She was in and out of jail so many times than she could count. In 1965 a new banning order was enforced that disallowed her to leave her neighbourhood. As a result, she could no longer be employed. With assistance from sympathizers Winnie sent out her daughters to a boarding school in Swaziland.

In May 1969 Winnie was apprehended during a night raid. She fell victim to the terrorist act of 1967, where arrests could be effected without warrant and people could be held in solitary confinement indefinitely and without access to counsel. Winnie spent 491 days2 in custody, most of which in solitary confinement, where she was kept in appalling hygienic conditions, was subjected to sleep deprivation and other forms of torture. Her incarceration coupled with sadistic methods of intimidation did not curb Winnie’s determination to remain defiant and politically active.

Banning orders, harassment, raids, arrests and other forms of pressure continued to be exerted on Winnie with the same virulence after her release from solitary confinement. But this campaign of intimidation did not have the desired effect. As a result of her continued political activism and resilience in dealing with the regime’s brutality, Winnie’s stature in the antiapartheid movement became admirable. By the 70s Winnie had become a role model for a new generation of disenfranchised youth that was helplessly frustrated with the apartheid. It is no coincidence that many among the youth who are so dispirited with today’s state of affairs in South Africa are vindicating Winnie’s as a means to assert their political aspirations.

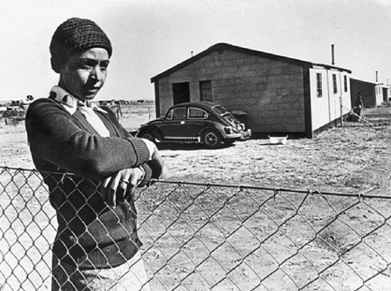

The Soweto Uprising of June 1976 signified the beginning of the end of the apartheid regime. Not surprisingly, Winnie was retaliated against by the regime for the violence and the political turmoil that ensued. Winnie was arrested and kept in custody for months. In May 1977 Winnie was banished in Brandfort, a remote location where she continued her activism by assisting and organizing the local community.

<> She was allowed to return to Soweto in 1986. She returned a heroine to one of the epicentres of the resistance against the ailing regime. However, Winnie never ceased to be a target. As her popularity grew stronger and the apartheid weakened, the government of the whites felt increasingly threatened at the prospects of Winnie and other radical elements gaining prominence in the post-apartheid South Africa. It is for this reason that the apartheid instigated a thorough campaign of smear, falsification coupled with infiltration of informants and agents provocateurs. Winnie had to be demonized systematically at all cost. In retrospect it is essential to recognize that the government of the apartheid, however debilitated had a clear vision as to the future of the country and took very seriously how to steer the transition to majority rule. This is a pivotal point to understand why so much effort has been invested to vilify Winnie. Winnie represented what the government of the whites feared the most, a threat to their privileges and social status. It is in this context that Winnie becomes a target and is subjected to tremendous pressure in the midst of chaos and violence prevalent towards the end of white minority rule. |

| Winnie Madikizela-Mandela during her exile in Brandfort in 1977 |

Today’s South Africa has not fundamentally altered the economic relations and social inequalities inherited from the old regime. Only the segregationist aspect of the regime was shed, as it is not critical to capitalist rule, where capitalist exploitation continues to be excruciating to this date. For this superficial transformation to occur the regime of the apartheid ferociously targeted those that it deemed a threat to the perpetuation of its economic interests. Winnie was the very embodiment of that threat and as such it had to be associated with barbarism, subversion, strife, violence and, finally, with murder. The apartheid used every possible means at their disposal to engender a demon in the narrow minds of those too scared to lose their possessions. What is, however, tragic lies in the fact that many in the ANC, who were all too eager to negotiate only to eventually betray the movement of national liberation, chose to echo the mythology created by the apartheid. It was this that Winnie was most indignant at, and rightly so. Winnie’s vilification and defamation did not come to a halt with the fall of white minority rule. Regrettably, Winnie continued to be harassed by those, now in power, who were supposed to liberate the black majority from poverty and exclusion, but instead chose to profit from the economics of the apartheid. There is a perverse logic behind this vicious opprobrium. In embracing neo-liberalism, the government of the ANC betrayed the struggle for national liberation, thus, perpetuating the economics of the old regime.

Early on during the transition Winnie and others in the ANC showed dissent from the way the negotiations were conducted and even more so when in time it became evident that the black majority was not to find relief from its economic alienation. Winnie and the likes not only threatened the apartheid, but also those that came after to benefit from the economics of exclusion that the apartheid itself was based upon. It is for the reasons of this objective connection that Winnie’s torment did not end with the establishment of the government of the ANC.

Winnie’s uncompromising stand against the apartheid scared many in the ANC and the anti-apartheid movement. Already in 1989 Winnie was lambasted by the United Democratic Front (UDF), as allegations of the kidnapping and murder of Stompie Seipei were leveraged against her. The UDF, a major mass anti-apartheid coalition, accused Winnie of “violating human rights in the name of the struggle against apartheid”.

In 1990 she was charged with kidnapping and in 1991 she was convicted, although the six-year term was reduced upon appeal to a fine. The ANC Women’s League sidelined Winnie by electing Gertrude Shope as its president. Nevertheless, Winnie was elected president of the Women’s League in 1993 and her tenure lasted for ten years.

Winnie was further humiliated, now under the government of the ANC, when forced to testify in front of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC concluded that “Ms Winnie Madikizela Mandela politically and morally accountable for the gross violations of human rights committed by the Mandela United Football Club” and that she “was responsible, by omission, for the commission of gross violations of human rights”. The TRC went further in making Winnie responsible for crimes against other members of the anti-apartheid movement as well. While Winnie was victimized, the TRC failed to appropriately expose former president De Klerk for his complicity in crimes against the South African people, not to mention the fact that former president Botha, De Klerk’s predecessor, blatantly refused to testify. The hypocrisy and double standards upheld in the process were, without a reasonable doubt, politically motivated.

In 1992 Winnie resigned her positions at the ANC after being accused of issuing unwarranted payments to her deputy. In April 2003 Winnie was convicted on 43 counts of fraud and 25 of theft for an alleged scheme to the tune of 100,000 USD, an appeal that she would win later. Winnie always denied direct involvement, or personal gain in these illicit activities. Nonetheless, it is ironic to see how Winnie was made accountable for amounts that pale in comparison with the sheer size of corruption in South Africa. One wonders why a person is convicted for a petty crime while billions have been obliterated due to endemic corruption in both the public and private sectors. It is hard to believe that the application selective standards were not politically driven.

It is now known that the apartheid’s police was heavily involved in discrediting Winnie by passing false allegations to news outlets regarding heavy drinking and promiscuity. This was done systematically in order to create a distorted perception of the fighter. Unfortunately, this was eventually picked up by her political opponents in the ANC. She was accused of multiple love affairs before and after the release of Nelson Mandela. These allegations were effectively used by some in the leadership to prevent Winnie from attaining significant positions of responsibility in government. As a matter of fact, the highest office she attained in government was that of Deputy Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, which she held briefly.

Shocking revelations aired on South African TV right after Winnie’s passing pertaining to how the apartheid’s intelligence services were directly responsible for the smear campaign against Winnie. Debates revolving around Stompie Seipei’s case have reignited in the light of this and other revelations. It seems evident that apartheid agencies had successfully infiltrated the Mandela United Football Club, which had become infested with agents provocateurs. It is believed that the man who killed Stompie, Jerry Richardson, the so-called coach of the Mandela United Football Club, was himself a police informant. The National Police Commissioner George Fivaz revealed this fact to the TRC. Other testimonies also attest to the role of the apartheid’s police in the violence that pervaded Soweto those days. The fact of the matter is that to date no credible evidence has been put forward to incriminate Winnie in Stompie’s assassination, or that of any other activist. In the words of George Fivaz, who upon being appointed National Police Commissioner in 1995 reopened the investigation: “There was not a single piece of information that fingered Winnie to say she was responsible... maybe personally responsible... for the murder, that she gave instructions for Stompie to be eliminated”. Winnie had approached Joyce Seipei, Stompie’s mother to tell her she was sorry for what had happened to her son: “When someone says ‘sorry’, you are compelled to forgive them. But in this case, Mama Winnie didn’t do anything, yet she came and humbled herself before us and said sorry for what had happened^ Mama Winnie was more concerned with seeing the children get an education and she was willing to facilitate that”. Joyce, as many others in South Africa was shocked by Winnie’s passing. She visited her house in Soweto to sign a condolence book wearing a shawl with the colours of the ANC and photo of Winnie.

Recent revelations have precipitated widespread indignation in South Africa. It was not just the fabrication and manipulation, which was obvious to many, but the fact that those in power decided to wait for her passing to let the truth out. Many in positions of responsibility in the post-apartheid period took advantage of the distorted perception of Winnie created by the apartheid regime for their own benefit. In an emotional tribute to her mother, Zenani Mandela-Dlamini stated: “Lies that have become part of my mother’s life^ and this was when we saw so many people, who sat on the truth, come out one-by-one to say they’d known all along that these things that were being said about my mother were false.”

The years between the release of Nelson Mandela in February 1990 and the elections in April 1994 is arguably one of the most violent periods in the History of South Africa. On the one hand, the government of the whites was meticulously identifying those in the anti-apartheid movement that they felt comfortable hold negotiations with; on the other hand, it was promoting black-on-black violence, division and demonizing those who were perceived as threats to the economic substrate of the apartheid. Two figures attracted the attention from those who were determined to perpetuate capitalist rule in South Africa: Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Chris Hani, who came to prominence as the Chief of Staff of the MK and had been elected the General Secretary of the South African Communist Party. He emerged as a prime candidate to replace Nelson Mandela. It was essential to the government of whites that these two powerful figures of the antiapartheid movement be neutralized before power was to be relinquished to the ANC. The first was vilified by means of a ferocious campaign of smear and fabrication. The second was assassinated in April 1993.

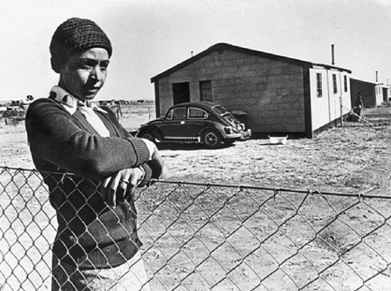

Two paths of development were envisioned for post-apartheid South Africa: neo-liberalism intertwined with neo-colonialism, or the implementation of the Freedom Charter by way of accomplishing the tasks of national liberation with the perspective of socialist construction. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Chris Hani were staunch supporters of the second route. Due to their unquestionable popularity among the blacks, they became stumbling blocks for the preservation of capitalist rule in post-apartheid South Africa and had to be sidelined and/or eliminated. Winnie’s pro-socialist sympathies were not a secret, as exemplified by Winnie’s admiration for Chris Hani: “We dreamt of a day where he would be president of South Africa”.

|

| Winnie Madikizela-Mandela next to Chris Hani |

Winnie reminisces about the day of Chris Hani’s assassination: “I was at home when Chris Hani was shot... It was clear that it was a complicated assassination, you couldn’t attribute it to the enemy completely”. Indeed, Hani’s assassination was a convoluted affair that could have not possibly been the result of the actions of two isolated individuals. Here the particulars of the terrorist attack perpetrated on Hani are not the issue. From the technical standpoint it seems plausible that two people planned and executed the operation. However, the political underpinning was the determining factor behind Hani’s assassination, where massive economic interests were at stake. Hani was not assassinated because he fundamentally opposed negotiations with the white government, which he did not, or because he promoted violence on whites, which he did not either, but because the white minority demanded a guarantee that the government of the ANC embraces neo-liberalism as its core economic policy. His elimination signified that guarantee and a precondition that was tacitly accepted. It is only when that guarantee was provided that negotiations finally converged and elections were held a year later. Hani’s assassination leveled the path towards today’s South Africa, where the black majority remains exploited and economically excluded. Winnie understood all too well the political motives that lay behind Hani’s assassination and its implications for the future of South Africa.

Winnie was critical of the state of affairs in South Africa and how little the government of the ANC has done for the black majority. In one of her last interviews she stated: “Something is very wrong with the History of our country. Something is very wrong with what we have done, how we have messed up the African National Congress”. This scathing verdict encapsulates the History of post-apartheid South Africa, as well as Winnie’s unwavering commitment to the cause of the oppressed.

History never forgets a true fighter for freedom and equality, no matter the slander.

Endnotes:

1 Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela studied at the University of Fort Hare and were suspended for student activism.