A. Bazdyrev

“Following the uncompromising path of Marx, Lenin and Stalin, who always valued classical art, Soviet architecture was able to overcome the bends of leftism, oversimplification in its own environment, opportunism of some of the old architects, and took the road of using the best elements of the old classical design”. L. M. Kaganovich

At the end of last year, we saw the 60th anniversary of an ordinary (as it seems to be) event that happened in the political and social life of the Soviet Union. On 30th of November, 1954, the Second Pan-Soviet Meeting of architects, builders and building materials producers marked a decision by the CPSU leadership to basically liquidate Soviet architecture.

The process was under the direct supervision of the then Secretary General of the Soviet communist party, N. S. Khrushchev. It was one of the first acts of Khrushchev’s revisionist policy aimed, in the long run, to undermine the socialist order in the USSR. Personally, the author is far from the thought that “Dear Nikita Sergeevich” was aiming at the socialist formation consciously. But the result of his anti-scientific, voluntarist, and basically Trotskyist policy was the destruction of many of the social devices that protected Soviet socialist society from bourgeois regeneration. The principles that allowed USSR to create one of the most powerful economies and to commit a grandiose cultural revolution that made the heights of human culture available to the huge masses of people, were revised.[1] The revisionist blow suffered by Soviet art was also heavy, and the one against Soviet architecture, the most “social” form of art, was particularly so.

Before the analysis of special features of development of Soviet architecture, it is necessary to outline the principles of Bolshevik policy towards art. It is obvious that communist parties must have a science- based, Marxist policy here to implement, so to speak, a cultural dictatorship of the proletariat. Otherwise, bourgeois molesting influences, often from under the most “revolutionary” mask, would rot the socialist art from within. An essential problem for the party was that the founders of Marxism had only “laid the cornerstones” as to the theoretical edifice of the future society’s aesthetics. Much had been done by such prominent Marxists as Mehring and Plekhanov. But more generally, the party leadership had to elaborate aesthetic preferences towards the artists on its own, out of the fundamental propositions of Marxism conscious of the specificity of historic moment and applied to specific forms of creative art.

Bourgeois modernism was the main enemy standing against Marxist aesthetics. Born in the last third of the XIX century, modernism became the main flow in the bourgeois art of the imperialist era. Reflecting the crisis of bourgeois mentality, the aesthetics of modernism has the following main features: refusal to portray reality in its essence, and thus of the realist method of creative art as such; rejection of the classical traditions of art; cultivating the image of the bad; naturalism [physiological approach towards the social - translator S note] and extreme subjectivity.[2] Against the modernist principles, the method of socialist realism was proposed by the Soviet art. It is characterised by: the propensity to reflect the reality in depth by means of realist artistic images; conscious commitment to the business of construction of a socialist society (partisanship of art); appropriation of all of the progressive styles from the art of the past;[3] expression, by means of art, of aspirations of the broad working masses (people’s nature of art); optimistic attitude, and democratism of the image structure.

Soviet art needed a firm, Marxist-literate guidance by the party, because it was socialist and therefore transitory: the one that is getting rid of the bourgeois spirit of the past but has not yet gotten rid of it completely. It has to be noted that with unavoidable reservations, such guidance was overall successful up until the mid-1950s. But after the death of I. V. Stalin, considerable liberalization of policies towards creative art followed, and modernist principles started to replace socialist settings. In the field of architecture, modernism displaced virtually everything related to the socialist realist method in the USSR.

The development of architecture in the USSR saw several important stages. Avant-garde was the chief road of development of Soviet art during the first post-revolutionary decade. Modernist language, as it seemed to many of the artists of the time, reflected the epoch of the dismantlement of the class society most adequately. Classical forms of art were associated exceptionally with the culture of landed aristocracy, and thus alien in class terms. The 1920s became the boom period for the “leftist” movements within all forms of art. Architecture was dominated by two modernist trends: constructivism and rationalism. Constructivism lead by M. Ginzburg and the Vesnen brothers announced a complete break with past architectural traditions (order system, national architect school) and proclaimed utilitarianism and “industrially” of architecture.[4] Creative problem-solving was done by the representatives of the constructivist school by means of merging various rectangular components without decoration. Following the “Five principles” outlined by the leader of the world’s architectural avant-garde Le Corbusier, the Soviet constructivist school preferred band- style glassification and flat roofing.

Photo 1: Zuev cultural palace (arch. I. L. Golosov, 1928, Moscow).

Photo 2: Office of Gosprom (arch. S. S. Serafimov et.al., 1928, Kharkov).

Rationalism lead by N. A. Ladovsky became a second modernist stream in the USSR. This trend, while sharing many of the constructivist principles, was more favourable to classical heritage and allowed for some decorativity.

The first five-year plan (1928-1932) saw wholly new branches of industry appearing in the USSR from scratch. Correspondingly, the task of construction of cities around new facilities appears. Frankfurt architect Ernst Mai was invited to the USSR to do the design. His group had attracted the attention of Soviet officials because of its experience in the construction of the so-called “workers’ homes”. However, the fact that the architect had to deal with orders from the big business trying to avoid a revolutionary proletarian uprising, was overlooked. The solution of the “housing question” on the part of big business was fully pragmatic: functionalism (the style practiced by E. Mai’s group) used maximum standardization as a means to cut costs. City blocks were made of multiply repeating “orchestra” of box- style buildings, deprived of any individual characteristics. The so-called “string construction” was also applied, when the sides of the buildings face the street.

As early as 1931, however, articles started to appear in the Soviet press that condemned such “soul-depriving” principles of construction. It was stressed that socialist cities should not make an impression of greyish gloom. Architecture produces a common environment for people to spend much of their time, whether it is work or leisure, and affects the formation of their personality. While constructivism and rationalism were considered as stages of the search for the socialist architectural method in the USSR and received a neutral attitude, modernist principles of functionalism were decisively rejected as alien to the task of socialist construction.[5]

The success of the first five-year plan and of the collectivization of agriculture allowed the party leadership to conduct socialist cultural policies more thoroughly. In 1932, a decree issued by the Politburo “On the Reconstruction of the Organizations of Literature and Art” marked the beginning of collectivization of the USSR’s cultural life. As opposed to a mess of cultural groups with motley ideologies, the Unions were created to become the promoters of party policies in the sphere of art. The Union of Soviet Architects was created in July, 1932. A year earlier, another event marked a radical turn in the architectural policies of the Soviet state. Architect B.N. Yofan won the first prize at the state-wide competition of projects to build the Palace of Soviets for a work completed in a classical order style. From this moment, we see the period of formation of the Soviet architecture that appropriated the best creative achievements of the past, inspired the pathos of socialist construction of the present, and aimed at the communist future. Following several intermediary stages, modernist styles were displaced by those addressing the world’s classical traditions of architectural design.

Pre-revolutionary Russian architecture was based on classical European

traditions creatively and uniquely interpreted by Russian architectural

designers. Masterpieces of the churches of the ancient Russia, the

park- and-palace orchestra of the Russian Empire, even the first trials

of modernist architecture in the form of the mansions of the Art Nouveau

- all have worldwide cultural significance. Soviet architects faced the

task of creating an architectural method of socialist construction

design that would lean upon the century-old artistic traditions of

Russia and Europe. The process was moving on with difficulties and was

not completed. However, in a short period of time Soviet cities were

completely renovated. Caring but, at the same time, creatively bold

treatment of the architectural traditions of the world allowed to

inscribe the buildings of the new socialist architecture into the

historical landscape of Soviet urban structure naturally and

harmoniously. In 1935, the General Plan of Reconstruction of Moscow was

approved which demanded to «start from the consideration to preserve

the basics of the historical city, but with deep reconstruction by

decisively ordering up the network of its streets and squares».

Principles of socialist economic planning gave a unique opportunity to

the architects to think in terms of the city as a whole by creating a

united aesthetic and living space.

Photo 4. A house on Mokhovaya street (arch. I. V Zholtovsky. 1934, Moscow).

Photo 5. “Revolution Square” station of the Moscow subway (arch. A. N. Dushkin, 1938).

It was the time when central avenues of the city got reconstructed, and its subway network increasingly expanded; in 1937, the Moscow-Volga canal went into operation; in 1939, the Agricultural Exhibition Centre was opened in northeast Moscow. All of the construction objects of that period impress by their resounding social nature. Lenin’s plan of “monumental propaganda” was being put in practice with such pathos and reach that Ilyich could not even have dreamed in the difficult 1920s. The image of a socialist city was to inspire the working masses and to pre-admire the harmonious, goal-oriented and beautifully noble life of the future communist society already today. The renaissance principle of the synthesis of various branches of art was put to practice. The best creative powers of the architects, artists, sculptors, engineers were thrown at the task of beautifying socialist urban space.

Classicism was the main style that Soviet architects addressed. But the

party insisted that the forms polished by thousands of years of human

history be filled with new socialist content. Absence of a theory of

socialist realism was felt sharply; positive requirements for the new

architecture were not clearly outlined. Sometimes, even the leading

Soviet architectural designers were subjected to criticism: I. V.

Zholtkovsky for “restorationism”, i.e. literal copying of classical

style techniques; A. V. Schutsev for eclecticism, uncritical

combination of styles from different epochs. Yes, by overcoming the

“diseases of growth”, the architectural method of socialist realism was

strengthening and crystallizing.

Photo 6. Skyscrapers. Manhattan, USA.

The post-war reconstruction of Soviet cities became the apotheosis of socialist architecture’s development. The mighty patriotic boom caused by the battles of the Great Patriotic War could not but to be reflected in the pathos of post-war construction. New buildings and subway lines were designed as monuments to the victorious People. In shortest periods of time, the Soviet cities destroyed by war came out of the ruins. The capital city acquired a new look; its architectural processes served as examples for the reconstruction of other USSR cities. On September 7, 1947 Moscow’s 800th anniversary marked the spectacular planting of the eight “high-rises”.[6] Stalin’s “Eight Sisters” formed the new dominant heights that did not interfere with the historical look of the capital city. Moscow’s high buildings differed from Western skyscrapers in principle. While the latter reject the artistic traditions of the past decisively and crash a city dweller with the sheer mass of their honeycomb floors, the designers of Moscow’s “high- rises” did address the treasures of worldwide, primarily Russian, architectural design, and built them in the Russian tradition of “marquee buildings”. The style of the Naryshkin era of the early years of Peter the First was most relevant to the task faced by the Soviet architectural designers. It is characteristic of mighty celebration-like vertical aiming combined with thorough elaboration of decorative details.[7]

Photo 7. High-rise building of Moscow State University (arch. L. V Rudnev, Moscow, 1953).

Photo 8. Main Street of Kiev – Kreschatik. Ukrainian SSR (arch. A. Vlasov)

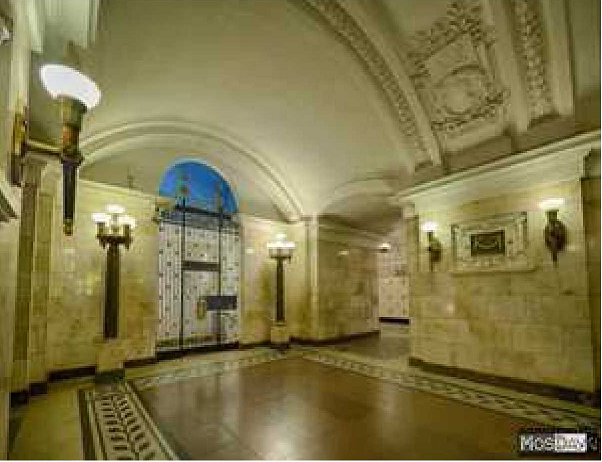

Photo 9. Kaluzhskaya (now Oktyabrskaya) station of Moscow Subway (arch. L. M. Polyakov).

Photo 10. Karl Marx Alley. Berlin. Architectural works of the 1950s.

Photo 11. A station of Pyongyang Subway. DPRK.

On March 14, 1954 the builders of Moscow Subway locked the Ring Line; one year later, the first series of Leningrad Subway went into operation. The triumph of the Soviet People – the Victor was incarnated in these products of architecture and engineering. The clothing of both underground and above-ground pavilions of the subway stations was spectacular. Underground palaces were beautified by the best artists and sculptors of the Soviet Union. High-value natural stone and rich decoration was used. The Victory by the Soviet People and the Socialist formation[8] was the main theme of these stations’ interior. Many of the stations, e.g. Kaluzhskaya (now Oktyabrskaya) resembled the sanctuaries of Greek and Roman antiquity with the Working Man[9] serving as an object of artistic worship.

Following the capital city, many of the Soviet cities were built or reconstructed in the style of celebration and triumph. Also, with the post-war formation of the Socialist friendship bloc, the method of socialist realism went international. As opposed to transnational modernism, with “internationalism” understood as complete rejection of both the worldwide classics and any uniqueness of national schooling, socialist architectural design derived internationalism harmoniously from creative rethinking of national architectural traditions, at the same time trying to extract and underline their mutual cultural “root” stemming from the humanistic traditions of High Classics.

Regular creative discussions on the improvement of the architectural method of socialist realism were also fruitful. It was a painful search for those architectural forms that would reflect the process of construction of a new classless society most fully. For example, in the post-war period, a negative tendency was growing in Soviet architecture that produced certain reasonable grounds (or excuses) for the 1954-55 “light-headed embellishment” accusations. Some architects approached the classical heritage uncritically and could not capture the border that separated the ahistorical, authentically humanist content from the superficial and class- limited. All in all, “the palaces and temples of the proletariat” must necessarily bear the aesthetical imprint of the socialist era, while it sometimes turned out that, by trying to reflect the greatness of the construction of socialist society, some architectural designers chose the simple way of replacing the creative search for architectural forms adequate to socialist consciousness by the (alien in class terms) gild of “public” luxury.

Having acquired the power, N. S. Khrushchev waged a broad front of struggle against all of the appearances (as he thought) of I. V. Stalin’s “personality cult”. Architecture became one of the first victims of the “bestial” Nikita. The architectural design of the 1930s through to the 1950s was strongly associated with Stalin’s name in the minds of the population; even now it is called none other than “Stalin’s style”, “Stalin’s imperial”, “Stalin’s baroque”. The denouncement of the “architectural luxuries” was allowed to defame a 20-year-long policy of Stalin’s Politburo in the field of urban development. On the other hand, resounding populist campaigns were needed by Khrushchev who lacked even one percent of Stalin’s popular respect; waging a massive programme of consumer housing construction was seen as a promising, in modern language, “PR-campaign”. In reality, Khrushchev’s merit in the solution of the housing question in the USSR is disputable, to say the very least.

But as it came out, the struggle against “architectural luxuries”[10] was waged against the Human who builds a communist society. Khrushchev did not realize the educational, personality-forming impulses of the new Soviet architecture. Apart from the natural formation, through everyday contact with the architectural environment absorbing centuries of achievements of human artistic and engineering genius, of a work-and-life culture cautious of harmony and beauty of High Classics, Soviet architecture performed another important function: she called from the future society centred around the all-sided development of its every member. And for this future, already tangible here and now, it was possible and indeed subjectively necessary to overcome the hardships of the period of transition from prehistoric human society to the real history. But as for the programme of mass construction of living space that served as a reason for this campaign of “liquidation of unnecessary luxuries”, as far as statistics is concerned, it failed just as many of those pursued by Khrushchev’s leadership.

Photo 12. “Open work house”: industrial residential project. 1940s.

Photo 13. “Khrushchevka”: industrial residential project. 1960s.

The exceptional importance of solving the housing issue in the USSR was understood by the previous leadership, too. In his last political economic work ‘Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR’ Stalin did raise the question of the “fundamental improvement of housing conditions” as a major prerequisite for transition to the communist society. And the issue, as everything suggests, was thoroughly inspected. According to professional opinion, USSR did not have the resources to solve this problem in a real socialist, i.e. robust long-run, terms in the 1950s- early 60s. A couple of five-year plans were needed to thoroughly prepare the necessary industrial capacity; time was also needed for the ideology of mass socialist housing construction to ripen, too. For example, the idea of large-block standardized industrial construction appeared long before the “mass Khrushchevization”. In 1940, one of the first buildings was erected based on this method: it is the famous “openwork house” on Leningrad avenue in Moscow. At that time, a decision was made to standardize separate architectural details instead of the project as a whole. Such principles of standardization were preferable to those of the later era when the faceless nature of the standard box-like living blocks became a theme for the famous comedy movie by Eldar Ryazanov [“Irony of fate”, 1975. On a New Year s Eve, a Moscow man mistakenly arrives in Leningrad, reports his Moscow street address to the taxi driver... With his standardized key, he opens a standardized front door of an apartment belonging to a lady having the same standardized address on Leningrad s “Builders ’Street” - translator’s note].

The new leadership thought that it could solve the problem simply by maximum saving on living space per person, quality of the interior, and that of the exterior through rejection of any architectural image. As a result, we have to admit that the socialist cities of the 1960s - 80s differ little from the provincial cities of developed capitalist states. The ideal was found in the French municipal housing that the French government, fearing socialist revolution, built for its workers to satisfy the minimum needs of a working man. It was small in living space and lacking any aesthetical attraction. It was built on methods tested and approved by the functionalist experiences of the 1930s decisively rejected by the Soviet society of the time. At the same time, statistics shows that despite the catastrophic drop in quality, quantitative rates of growth in the civil construction sector were falling all the way throughout the 1960s-80s. The only areas that experienced an increasing “mass construction build-up” were Moscow and to some extent several other major cities of the USSR. It was a logical consequence of the broad adventurous economic policies of Khrushchev’s group.

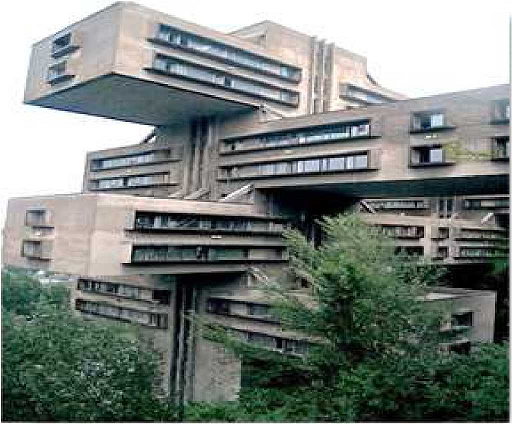

Photo 14. Residential housing on Begovaya St. Architectural style – “brutalism” (arch. A. Meerson. Moscow, 1978).

Photo 15. Highway Ministry of Georgian SSR. Style – “brutalism” (arch. G Chakhava, Tbilisi, 1975).

Photo 16. Typical high-storey urban development zone. USSR. 1970s-

Photo 17. Experimental high-rise building. “Ship-house” on Bolshaya Tulskaya. Moscow, 1981.

We thus see a partial rejection [it has to be noted though that the main achievement of the socialist society s housing policy, the inalienable right to housing, remained until the collapse of socialism in the USSR- A. Bazdyrev] of socialist principles of housing construction in the USSR. Soviet architecture ceased to play educational and propagandist roles, with all the positions conquered by Soviet architectural designers in the previous decades given away for the sake (supposedly so) of economic efficiency. From 1955, the process of the liquidation of the truly Soviet architecture begins. Many buildings planted but not completed before 1955, were mercilessly “stripped down” by the Khrushchevites: the originally planned decoration was either expelled from the final plan, or barbarically scratched down. Before, the best efforts by the architects and engineers were aimed at selecting the best samples of the past design to be used to express the ideals of work and life of a freed working man. From the second half of the 1950s they were redirected to the task of searching for perverted ways to cut costs, and to discover the poetry of panel boxes. The downhearted “box” landscape became a “norm” for the Soviet cities. By a decree as of Aug. 23, 1955, the Academy of Architecture was liquidated, and the Academy of Construction and Architecture was formed, thus reducing architecture to the status of a cheap appendix to industrialized construction. Key positions within architectural management were occupied by strangers; a severe blow was suffered by architectural education, too.[11] We can state that as a result of these actions by the Khrushchevites, the romantically socialist approach to urban development was displaced by one of the vulgar pragmatism. One of the brightest lighthouses of the future society of human’s all-sided development was extinguished.

Photo 18. Agricultural Exhibition of the USSR (after 1959- VDNKH). Pavilion “Azerbaijan SSR”, 1954.

Photo 19. Pavilion “Computer technology” (Pavilion “Azerbaijan SSR” reconstructed in 1967).

Photo 20. Pavilion “Livestock”. 1954.

Photo 21. Pavilion “Electrification”. On the spot of the Pavilion “Livestock” demolished in 1965.

From the second half of 1960s and until 1991, further active “integration” of Soviet architecture into the worldwide stream of architectural modernism takes place.[12] Perhaps no other side of the Soviet reality experienced such a vividly expressed counter-revolutionary tendency. The most extreme architectural experiments of Western modernism were taken as examples.[13]

The functionalist approach received a further boost. Housing was becoming more and more comfortable in terms of square metres per capita, communications and interior; yet, at the same time, more and more alienated in terms of aesthetics. Ryazanov’s “Builders’ streets” were engulfing the USSR by their colourless, dead, uniform blocks of high-rise boxes. Dehumanized architecture rusted the Socialist City.

Modernist construction development infiltrated the historical landscape in a barbarian way. Ahistorical in its essence, modernist architecture crippled the look of Soviet cities that had taken centuries to mature. One of the most vivid examples of such urban development is the “artificial jaw of Moscow”, a series of high-rise buildings on Kalinin avenue passing through the historical centre of the city.[14] In addition, architectural revisionism mercilessly destroyed monuments of truly socialist architectural design. “Reconstruction” of VDNKH is quite an example. A unique architectural complex combining the best samples of worldwide classical art with the unique charm of the national republics of USSR and RSFSR, was to be “modernized” to the jubilee of the October Revolution. In 1967, the classical look of many of the pavilions was crooked by the modernist “innovations” beyond recognition, while the unique pavilions of the Central Alley were simply demolished.

With counter-revolution victorious in 1991, nothing could hold back the further expansion of modernist architecture into Soviet cities, and the increasing destruction of their historical look. At the same time, a certain tendency of interest towards classical architectural design also picked up. Apart from the ultra-modernist construction, buildings are been erected in the classical and pseudo-Stalinian style. In 2014, Moscow saw the massive reconstruction of VDNKH, including an attempt to return, where possible, to the authentic architecture of 1954. Perhaps, such a controversial tendency can be explained by the heterogeneous nature of the new Russian bourgeois class. Its conservative wing is interested in support from both the conscious and unconscious pro-Soviet majority of the Russian society. In the eyes of this social group, vague and scattered as it may be, the socialist achievements of Soviet society become more and more attractive, especially in the face of the liberal free-all of the 1990s.[15]

The history of Soviet architecture is closely linked to the process of the rise and fall of the early socialist states. By overcoming the “leftish” cultural deviations of the period of early proletarian “siege of the sky”, Soviet architecture generated more genuinely socialist concepts of urban development, while bourgeois architectural modernism was given a determined battle. It became clear that all the highest cultural achievements of human prehistory should be preserved carefully for the future society and filled with new humanistic content. This process, with unavoidable deviations and casualties, progressed until the mid-1950s. But the Soviet architects were among the first who experienced the interception of political power by the revisionist wing of CPSU on their own back. Misunderstanding of the special ideological value of architecture by the political leadership led to the loss, on the part of the socialist society, of one of its most important spiritual guidelines.

The cultural and living space of Soviet cities started to be filled with modernist architecture alien to socialist aesthetics. The dialectical unity of architectural products being both the “shelter and the art” was perverted. Vulgar pragmatism of squared metres swallowed the romanticism of the “Sun City”. The spirit of socialism felt less and less comfortable in the cities rusted by the bourgeois modernism. But even now, after the victorious bourgeois counter-revolution, it is present vividly in the grandeur of the high-rise buildings of Moscow, the architecture of the great canals of the Volga, the dressing of the Leningrad subway, the main street of Kiev, and thousands and thousands of supremely beautiful buildings of the large and small cities all over the former USSR. Those are the monuments to a genuinely heroic era of the first siege of the world of total alienation. I wish to hope that time will come, and the ideals of true equality and brotherhood will materialize in the architecture of the reborn Soviet cities with unseen splendour, and the creativity of designers from the 1930s and 1950s will serve as a reliable lighthouse for the architectural designers of the communist future.

REMARKS:

[1] Undoubtedly, the Soviet society was not free from various disadvantages of a, however, objective nature. The harshness of high leadership was a condition of early socialism that appears and develops on an inadequate material and technical base in the face of the overwhelming forces of capital. Khrushchev, for opportunistic reasons, attributed those shortcomings of the party policy to the alleged voluntarism of one personality - Stalin, thus creating a more pernicious “anti-cult of Stalin” while chopping down the “green sprouts of communism” in many areas of Soviet society.

[2] As K. Schwitters, leader of one of the modernist trends, said: “Anything I spit down will be art, because I am an artist”.

[3] Socialist realism is not a “style” in a narrow sense of this word, but a method that includes the principle of absorbing all the valuable artistic achievements of the past.

[4] As Le Corbusier, leader of the Western architectural modernism, said: “House is a car for living”.

[5] It is functionalism that was going to become the leading architectural principle of the post-Stalin USSR. The image of the city of that time, unfortunately, gave the counter-revolutionary intellectuals a real opportunity to call certain parts of Soviet reality by such diminishing characteristic as “Sovok” (spade).

[6] By 1953, seven of the eight buildings were completed; the administrative building in Zaryadie was under construction, and would be demolished after 1954 (with its materials used for the construction of the “Luzhniki” stadium) and replaced by the “Russia” hotel designed in the functionalist modernist style by the same architect.

[7] During the epoch of Peter the First, Naryshkin’s baroque was the style that connected the architectural traditions of the older Russia with the new European baroque settled in Russia after Peter’s reforms.

[8] It was characteristic for subway stations of that time to address the triumphal architectural style of the Imperial Rome.

[9] The image of I. V. Stalin was significant in the decoration of subway stations and many architectural complexes such as the New VDNKH, Volga-Don canal, etc., and, according to many of the contemporaries of “Stalinian architecture”, did not cause negative emotions, as he was perceived as both a symbol of Victory and “our own man” for the labourers. Within certain boundaries, the “personality cult” was of spontaneous and natural origin.

[10] The programme document that put an end to socialist architecture on November 4, 1955 was named “On the liquidation of luxuries of design and construction”.

[11] During Stalin’s time, the subject of architecture taught by the leading architects of the USSR was obligatory for students of the High Party School.

[12] Simultaneously, a counter-process of using certain elements of classical architectural heritage, e.g. in the decoration of some of the subway stations, picked up, though of restricted character. It did not define the main process of development (degradation) of Soviet architecture.

[13] Interesting fact: it was Western modernism but not the Soviet avant- garde experience of the 1920s and early 30s, that was taken as the example. Soviet avant-garde with its humanistic influences imprinted by the revolutionary epoch, was left out of consideration.

[14] Fortunately, a similar project of “modernization” of the historical centre of Leningrad (Nevsky) did not materialize.

[15] It is with this fact that the increasing pro-Soviet rhetoric is connected: the return of the music of the Soviet anthem, of the red flag of Victory to the armed forces, promises by the authorities to bring back the historical name of Stalingrad.

Translated from the Russian by Vitaly Pershin