Turkey

Labour Party (EMEP)

Democratic Movements and Socialism

The bourgeoisie and its ideologues are trying to explain every social incident and phenomenon as a new “end”

of classes and the class struggle. They keep repeating that classes are

dead and will never return, in order to wipe away from the

consciousness of the working people even the possibility of ending the

economic and political rule of the bourgeoisie.

With the collapse

of the revisionist USSR, Francis Fukuyama, an ideologue of imperialist

barbarism, announced that the war between the working class and

bourgeoisie had ended, and called it the end of history and ideologies.

The propagandists of the New World Order and critics of “real socialism”

have cried in unison that national borders were going to disappear and

that the free market will bring prosperity and peace to the world. But

the general tendencies of capitalism were in motion even before the ink

had dried. The result was wars, national enmity, exploitation, poverty,

unemployment and hunger.

Using scientific and technological

developments, the temporary defeat of socialism and some new cultural

components as a base, they proclaimed the working class dead and the

end of class differences, replaced by differences of status, income and

cultural identities. While discussing the struggle of oppressed

identities, they ignored the relationship between these identities and

capitalism, and also presented these movements of identities as proof

of the end of class movement.

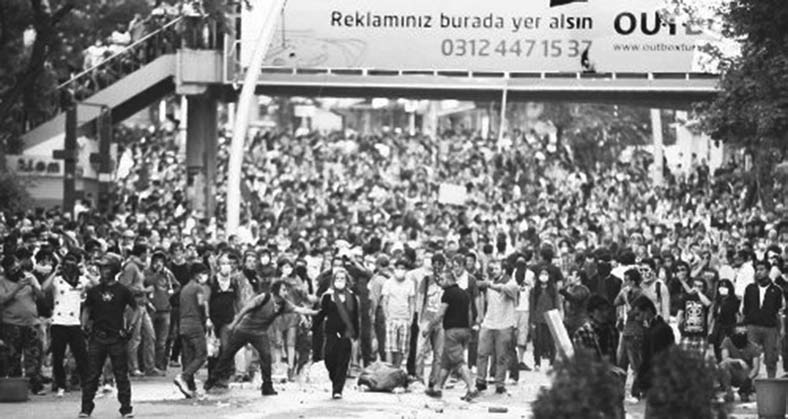

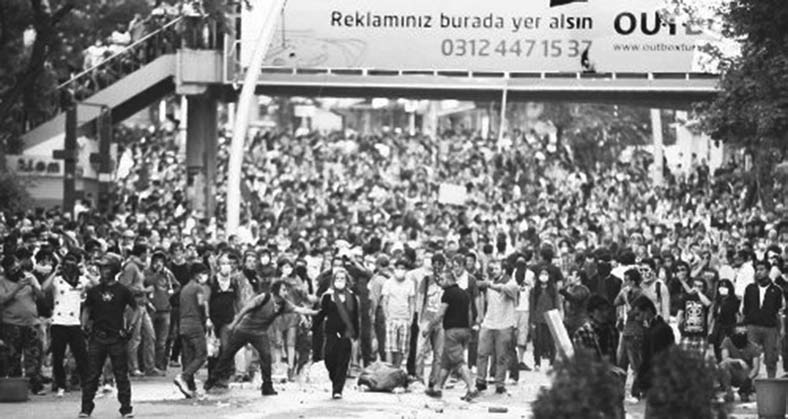

The insurgencies that started in North Africa in 2011 and spread to

almost all of the Arab countries showed the world that the era of

revolutions had not ended. However, the bourgeoisie tried to reduce

these movements to Western type demands for capitalist democracy,

denying their opportunity and potential to develop. The same could be

said about the 2013 Gezi Resistance in Turkey. Occupy Wall Street and

the rising mass movements against austerity in Greece, Italy and Spain

are defined in essence not as the reaction to the results of capitalism

but as a movement of anger against neoliberalism; an insurgency of the

educated bourgeoisie, of professionals or of the “majority.”

The rising and undeniable worldwide movements for women’s rights, for

protecting nature and the environment against capitalist pillage, the

movements of oppressed nations, ethnic identities, religious groups,

sexual orientations, etc., are presented as indicators of the ideology

of globalisation and the majority of civil social. They are all used as

proof that the class struggle is an “archaic” ideological argument that

has been left behind. The alternative globalisation movements have been

placed in a position where, with the slogans of “another type of globalisation” and “a better world,” they are dependent on reforms by international institutions, where their points of view are limited to reforms.

Leaving their specific aims and programmes aside, the theories that

define these movements –detached from their objective roots and

ignoring their relationship with capitalism and the class struggle –

reject an analysis based on the struggle between the bourgeoisie and

the proletariat, the two main classes under capitalism. According to

the “new social movement” theorists, society has gone through deep-rooted changes and does not fit the “model”

put forward by Marx. The working class – to which Marx attributed the

revolutionary role – has lost its influence and has become just one

more part of society through labour parties. Hence these movements have

only one choice: a “radical” or “moderate” struggle for democracy!...

In fact, despite its position in the struggle for democracy, its “good

intensions” and “attempts,” any movement that is not based in the

working class and does not aim to destroy the networks of capitalist

relation and to establish collective production relations, will not be

able to overcome the limits of the ruling bourgeois capitalist system

and cannot consistently carry through its own democratic demands.

Movements of Cultural Identity

Social movements, which are historically as old as class societies, are

expressions of unrest, of demands for needs that have to be met and

fulfilled. Insurrections, riots and revolutions have existed throughout

history; they have had a significant impact on shaping social life,

they have been the “engine” of change, to use a common expression.

The wave of rebellions that spread through the Arab world, starting

with the suicide of Mohamed El Bouazizi in Tunisia on 17 December 2010,

and to a certain extent the Gezi Rebellion, have been seen by some

authors and intellectuals as a milestone in the transition from

modernism to post-modern society in the Middle East; they have been

compared to the Europe of 1968. According to this analysis, the

millions involved in the Arab rebellions went into the streets not for

economic reasons or ideological objectives but with pragmatic demands

that concerned their daily lives. Without demanding Power, they carried

out a post-modern struggle using “new methods”

such as occupying squares. Likewise, despite its differences with the

Arab rebellions, the Gezi Resistance has been seen by many thinkers as

a step towards post-modernism and its forms of opposition in Turkey; in

other words, it was a step towards “new social movements”.

The concept of “new social movements”

is based on the idea that movements such as feminism, anti-racist,

environmentalist, animal rights, anti-nuclear and peace movements – on

the rise since the 1970s – have broken from the “old” social movements based on the class struggle, primarily of the working class, and that they are an ontological “new” concept. They are inspired by post-structuralist and post-Marxist tendencies of the 1970s.

The concept of “new social movements”

is based on the idea that movements such as feminism, anti-racist,

environmentalist, animal rights, anti-nuclear and peace movements – on

the rise since the 1970s – have broken from the “old” social movements based on the class struggle, primarily of the working class, and that they are an ontological “new” concept. They are inspired by post-structuralist and post-Marxist tendencies of the 1970s.

There are two different views regarding the relationship between the “new social movements”

and classes and class struggles. The first, represented by Claus Offe,

sees them based on the new middle classes. The second uses the argument

that these movements do not have “an economic base,” hence they cannot be explained by the terminology of classes but rather by identities and values.

According to Offe, the opportunities of consumption and the monotonous structure created by the “society of prosperity” has led to “new”

social movement that stress the non-economic values in life. Values

such as identity, participation and fulfilling ones potential have come

to the fore.

The most important representative of the identity approach, Alain Touraine, sees the “new social movements” as based on the paradigm of the post-industrial society. Movements arise in the new society and the domain of broad “civil society,”

instead of the state as in the past. According to him, the struggle is

to transform civil society; their aim is not to take state power. As

the distinction between private and public spheres has been eliminated

in post-industrial society, new conflicts arise on the basis of

identities that are not visible or excluded from the public sphere.

Societies and the world in general are not under the rule of the

bourgeoisie, but of the state.

First, the claim that the “new social movements” are “new”

and that they are based on post-modern or post-industrial social

foundations has no objective foundation. One main assumption of the “new social movements”

is that modern capitalist society has been replaced by a post-modern or

post-capitalist society. Therefore, the class struggle has lost its

relevance or at most has the same importance as any other forms of

struggle. State power, rather than being the representative of a class

or an alliance of classes, has become a “biopower” that tries

to control all areas of society and life. This framework is the main

argument of post-capitalist, neoliberal propaganda, which claims that

the society we live in has become independent of capitalist class

relations, that differences between classes have disappeared.

Rather than decreasing, class conflicts all over the world are becoming

sharper along with the increase in exploitation, poverty and

unemployment. Rather than the main characteristics of capitalism

disappearing and the erosion of class divisions, the last 40 years of

neoliberalism has brutally exposed the essential characteristics of

capitalism. The number of people in control of the means of production

is constantly shrinking and billions of people in all countries

throughout the world do not own any means of production. They have

nothing but their labour power to sell; they are forced to enter the

capitalist market.

In China, India, Turkey, Egypt and Brazil, in parts of the world that

began developing capitalism rather late, just within the last 15 years,

millions of peasants (hundreds of millions if you think of China and

India) have been thrown off their lands. They have migrated to the

cities to join the ranks of the armies of the unemployed or to work in

the informal sectors.

Privatisations, liberal deregulation policies, the removal of all

“national” barriers in the way of capital, the burdening of society

with the costs of the deteriorating environment, the reduction of

workers’ wages, flexible and unregulated work, the appearance of savage

19th century working conditions at a more advanced technological level,

every day shows clearly the reality of the existence of classes, the

chasm that exists between classes and the struggle between them. From

this perspective – despite scientific, technological developments and

other “new” phenomena – capitalism continues to exist and maintains all its essential characteristics.

There are important parallels and elements of continuity between those “old” movements that began in the 18th century and those deemed to be “new”. For example, the focus of the “new”

social movements on identity, using different tools and the

politicizing of daily life, were also visible characteristics of

national movements existing since the last century.

To approach

issues that are the focus of “new” social movements as if they had

never existed, been discussed or struggled for in the “past”, is at the

least an exaggeration if not a fallacy. For example, the women’s rights

movement is focusing on working conditions and salaries, which is

something the workers’ movement has focused on for decades. Likewise,

groups that protest against the military power of the USA see their

primary aim as economic equality around the world.* The focuses of the “new social movements” such as personal liberty, equality, participation, peace, etc. are not only not “new”

in the way they are portrayed but are inherited from the progressive

movements of the bourgeoisie and the working class. Many issues that

seem new today have been main elements of social movements of the past,

and economic issues deemed to be in the past are very important

components of today’s social movements.

* Taken from J. J. Macionis, Sociology, 14th edition, 2012, p. 555.

The demands for recognition

of identity are also not a phenomenon that only began in the 1970s.

Movements in 19th century of ethnic minorities, women and for religious

freedoms regularly put forward demands regarding autonomy and identity.

It is not possible to analyse the movements of different sections and

classes in society and their actions and rebellions by isolating them

from the economic production relations, social conditions and various

other conditions in which they have arisen and developed. While the

existence and movements of classes – this applies also to individuals

and groups – are shaped by the material production conditions in which

they exist, the individual and combined actions and movements of these

classes, individuals and groups also influence changes in these social

conditions. The economic and social conditions, the political and

economical-vocational organisations, the ideological factors,

orientations and tendencies, the “cultures”

and perceptions that have been taken over, reshaped and reproduced

within the conditions of these movements, all play a role in the

development of interclass relations. Furthermore, these relations and

conflicts do not exist or take place at whatever time or in any

condition but within the society from which they emerge.

Economic

relations and social conditions are the foundations of social

movements. The social division of labour and the organisation of social

production – the social character of production, production as the

collective labour and creation of workers from interconnected and

linked sectors – are created primarily by the proletariat and this

makes it the primary force of the social movements. This relationship

with the material conditions of production of social movement advances

it from as abstract movement of isolated individuals, separated from

one another, into their collective movement. Actions, thoughts and

morals of individuals cannot be isolated from their conditions of life,

from the class relations and conditions of production that give rise to

them. “Even something that an individual achieves is in essence today also a product of society…”

Humans can only be brought into conflict and struggle with other humans

– groups of humans – by material conditions of life. The struggle

develops between them and they start “wars” in connection with

their demands and objective, according to their polarised positions

within the existing system of production.

For instance, the Gezi Resistance of 2013 in Turkey, which was the subject of attempts to camouflage it as a “new social movement”…

The resistance began locally and spread to one of the most important

centres of Turkish capitalism as the “collective” struggle of the

working class and other labouring sectors, oppressed and subjected to

different types of pressure, against monopoly reaction. It was a

struggle against a government that used political pressure and police

brutality. Independent of whether the oppressed and exploited reacted

as a “crystallised” expression of their financial-social demands, it

was not a movement isolated from the relationship between classes and

the intermediate strata and sections; it was not an “oasis in the desert.” To reduce the resistance to a question of whether it was “expected” or “unexpected,” or to represent it as a “new development” or “new evidence”

against the class struggle or the historically revolutionary role of

the working class within this struggle, would mean either not paying

attention to or ignoring the class context of the social movement and

its relationship with the material conditions of production; it was a

movement of the exploited and oppressed social sectors, primarily the

working class.

What Do the Peoples’ Uprisings Show?

First, that the era of revolutions has not ended; on the contrary that

it is current, that capitalism cannot bring prosperity and peace to the

people and that the relationship between democracy and the market has

no reality.

How sufficient are these social movements, such as the insurgency in

Tunisia and Egypt or actions demanding reforms in Spain, Greece and the

USA, in meeting the demands and the overcoming of the limits of

capitalism, despite significant participation of the workers and other

labouring people?

According to some post-anarchist thinkers covered with “anti-authoritarian” rhetoric, these movements are evidence of the end of the revolutionary action of the working class. They show that the “majority,” the petty bourgeoisie, the “salaried bourgeoisie” or irreducible identities make up the foundations of social opposition, or in the words of John Holloway, “justified” the conditions of the paradigm arguing that it is possible to “change the world without taking power”!*

* John Holloway, Change the World Without Taking Power, Pluto Press, 2002, USA.

For example, according to Negri and Hardt, these movements are the resistance of the “majority” against the “Empire.” In saying “we try to use the concept of majority to define subjects like Gezi” Hardt explains the “Gezi Resistance” as demanding “a new democracy” that overcomes the limits of capitalism;

“On

a positive note I can comment on two or three main characteristics. The

first is the concept of majority or plurality as you mentioned, the

second is demanding a new type of democracy. Maybe this means that the

democracy we are subjected to is insufficient, degenerate and wrong but

at the same time accepting our yearning towards another democracy. I

think that from some perspectives, setting camps through forms itself

involves demand for partnership. Put another way, this is a refusal of

private property and liberalism and also the government control seen as

their alternative. Besides, the building of partnership areas

especially in urban areas brings together open access, shared

responsibilities and democratic governance among with it.”*

* Interview with Michael Hardt, “Organising the Multitude Is Difficult”, in Mesele Dergisi, June 29, 2014

In their work, “Declaration”,*

Negri and Hardt salute not only the Gezi Resistance but also the Arab

insurgencies and the peoples’ movements against austerity programmes as

actions and organizations of the “majority,” that they are oriented towards the “common good” against private property.

* Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Declaration, 2012.

While describing the Arab insurgencies as “direct riots,” Alan Badiou points to their potential of turning into “historical riots.” Badiou defines a riot or insurgency as a disruption of a continued routine, an “event” that breaks with the situation, that is, with governmental rule. The “event” in Badiou is that which breaks with and opposes government control.

In his book “The Rebirth of History,”

(2011) he states that the Arab uprisings, in their internal

organisation, have gone beyond class structures and that they are

communist movements because they called for the realization of the

common interest of all humanity.*

* Alain Badiou, Rebirth of History, Verso, London, 2011

The unification of people from different classes, leaving aside their

class differences, the search for a “real” democracy in the face of

government representation and its imposition of violence, and the

incompatibility of this demand for democracy with capitalism, provides

a great potential for a “communist” movement according to Badiou. As if

the workers’ abandoning their class identity in search of a democracy

without classes that opposes capitalism could lead to a communist

movement.

The reason for Hardt to see the Gezi Resistance as “communist”

is the link that he makes between the demand for democracy and

communism. According to him, communism – and socialism as its first

stage – is not the working class abolishing private ownership of the

means of production after the seizure of political power; it is the

building of an independent communal society by people from different

classes who turn their backs on the state. From this perspective, for

him, the democratic fight against the government is primary while

abolishing the regime of private property is secondary!

Hardt’s

observation that Gezi Resistance has started the search for an

alternative democracy is correct. Furthermore, from the perspective of

gaining rights through direct struggle against the system of bourgeois

representation and achieving its demands through a mass struggle, Gezi

does harbour the seeds of real democracy. Nevertheless, these are only

perspectives and seeds. The movement has to have an anti-capitalist

perspective to succeed.

Adopting a simplistic approach, Hardt, Negri and the libertarian

theoreticians conclude that the occupation of Gezi Park and the

establishment of a “commune” of struggle indicate the movement’s

opposition to private property and liberalism; that the camp and forums

represent a demand for collectivism. As they put the State at the

centre of the class struggle, they make the mistake of characterising

every riot or insurgency against the government or some expressions of

the state as inevitably anti-capitalist.

The libertarian theoreticians, in putting the objective conditions of

the movement in second place, see the movement itself as the

confirmation of the “alternative society”. According to this viewpoint, “the movement should conquer its own space and control it”. Today’s libertarian politics sways between a caricature of anarchism and moderate reformism.

These ideas define a “communism” that is above classes and within

capitalism, based on the postulate that communism founded on working

class struggle is bankrupt. Anarchist or post-anarchist thinkers such

as Murray Bookchin, Bruno Bosteels and John Holloway reject the

organisation of the working class as the ruling class; they put the

conflict between the power and society at the centre, promoting “communal groups” that turn their back on the State.

However, these communal groups cannot overcome capitalism on two

issues. First: they put forward a small, temporary communal group that

is not built on the overthrow of the capitalist authority and the state

apparatus, but on a kind of withdrawal, turning ones back or

disengaging from the state apparatus. It cannot be claimed that a

communal group that fails to overthrow the capitalist state and abolish

capitalist relations overcomes or will overcome these relations by

“turning ones back” on them.

Second: the communal group established is not a new and consistent

network of social relations but rather the relations of collaboration

in the struggle. The Gezi “commune,”

for example, is not a form of social relations that creates the

material and non-material production or reproduction of society; it is

more of a communal organisation of struggle and consumption.

Could They Not Have Advanced?

Of course, the democratic character of a movement does not exclude the

possibility that it could advance or gain the potential of overcoming

capitalism, with new components and a new programme.

If the environmental or women’s rights movements, or the struggles

against imposed life styles, lack the necessary consciousness and

programme to target the source of their problems, they will remain

imprisoned within the forms that gave rise to them, which are the

direct result of capitalist character of the relations of production.

Social movements can overcome this only if they do this in the struggle

and realise that the political, democratic reforms cannot really meet

their demands and hence they orient themselves to overcome the limits

of capitalism.

However, in the rising democratic movements and rebellions around the

world, starting with the Arab uprisings in the autumn of 2011, this

tendency has not been strong enough. Despite their partial successes

and deep rooted changes, the fact that they were not able to finally

win is due to the structural weaknesses of these movements.

However, in the rising democratic movements and rebellions around the

world, starting with the Arab uprisings in the autumn of 2011, this

tendency has not been strong enough. Despite their partial successes

and deep rooted changes, the fact that they were not able to finally

win is due to the structural weaknesses of these movements.

In Egypt, millions took to the streets and Tahir Square to demand the

resignation of Hosni Mubarak, the dictator who ruled for 30 years. This

was followed by the rule of Muslim Brotherhood under the presidency of

Mohamed Mursi. When millions took to the streets again, as their

demands had not been met, the Chief of the General Staff Abdel Fattah

el-Sisi declared himself President through a military coup. Likewise,

despite the struggle of millions of Greek workers against austerity

measures after the crisis of 2008, and despite the occupations and mass

demonstrations, the result – at least for now – is the Syriza

government that is implementing the austerity measures and had to call

a new election due to its weakness. We could give many more examples.

This does not mean that social movements have not achieved successes.

Through these resistances very important and historical gains have been

made. The people have gained experience in struggle in the difference

between allies and enemies; submission has been gradually replaced by

consciousness in struggle; they recognize that they can bring down

governments through their own actions; they are progressively

developing the idea of socialism within the struggle. However, the

anti-democratic and reactionary governments that people stood up

against have been replaced by new ones and the people’s main demands

have not been met.

One of the most important characteristics of the social movements that

emerged since 2011 is that the movements have not had a consistent

common programme that the masses could unite behind. A programme not

only of demands but one that the people carry out and take part in

organising, even in power, adopting a communist perspective aiming at

the abolition of capitalist production relations that are at the root

of the lack of people’s democracy, of socio-economic poverty and other

problems. Of course this perspective cannot be accomplished through the

outbreak of a spontaneous, unorganized movement, but only through one

influenced and led by a communist organisation and programme.

For example, the Gezi Resistance did not aim to overthrow the state and

establish the rule of those classes and strata allied with the

resistance. In other words, it could not do this because of the lack of

its own organisation. Supported by various classes and strata, the

Resistance, although it demanded a general democracy, was not a

movement for power but an outbreak of rejection and anger. Concrete

demands for the protection of Gezi Park were a symbol of making the

government retreat and the slogan that the “government must resign”

showed the anger against the government. But the movement did not have

a clear perspective on the question, for example, of the replacement of

the AKP [Justice and Democracy Party] by another bourgeois party such

as the CHP [Republican People’s Party].

From this perspective, the fact that the movement did not “aim at power” was not a matter of “naivety”

but one of its main weaknesses, along with not targeting capitalism

directly. The class composition and the relation of forces within the

movement were determining factors in this. The fact that the

determining elements of the working class did not take part in the

movement with their own demands and organisations was a big handicap in

its ability to lead and organise the movement towards taking power and

its programme.

The arguments to “stay away from power and its corrupting influence,” of “autonomy” and of “creating non-hierarchical living spaces,”

put forward by the bourgeois liberal and libertarian individuals and

groups inevitably transformed it into praise for the spontaneity and

disorganised character of the movement. From this viewpoint, a

resistance that does not aim at power could create alternative,

exemplary communist living spaces within a semi-anarchist framework and

thanks to this, supposedly transform the country!

However, “the fundamental question of every revolution is that of power”

(Lenin). A movement that does not seriously put forward the question of

power, that does not aim at it in theory and practice, regardless of

its subjective wishes, ideals and demands, is condemned to remain

permanently within the limits of capitalism. The Gezi Resistance, which

was an indirect form of class struggle, has shown this once more.

A

democratic movement that puts forward the question of power could lead

to positive results, at least in terms of winning democratic demands.

However, a democratic movement whose perspective does not go beyond

capitalism cannot even resolve the political democratic demands that it

sets out to resolve – neither breaking links with imperialism, the

women’s problem, the demands for the future of youth – in a real and

concrete manner. Under the conditions of bourgeois reaction, many

demands that could possibly be resolved under capitalism are rooted

within capitalist relations of production, and are constantly produced

and reproduced by the existing socio-economic structure. Thus in

practice it seems impossible to resolve them (though theoretically this

possibility exists). Therefore, a socialist programme, perspective and

leadership needs to be in place for democratic political demands to be

realised concretely, overcoming the existing socio-economic limitations.

From this perspective, although the movement as a whole puts forward demands and slogans for “real democracy” and “popular aspirations”

directed at the political structure, they forget the bourgeois

capitalist nature of production relations. A democracy in which the

exploited millions are in power is only possible through destroying the

bourgeois dictatorship based on the private ownership of the means of

production.

The demand for a “real democracy” has not

gone beyond the rejection of the present false “democracy”. This shows

once more the importance of the conscious participation of the working

class in the movement, which the Communist Party makes advance, while

paying attention to the different tendencies towards political

democracy and gradually to the rejection of all forms of bourgeois

rule. The failure of these spontaneous rebellions to even win their own

demands show that capitalism can only be destroyed under the leadership

and programme of a Communist Party that has established strong ties

with the working class, that understands the tendencies among the

masses and is skilled in leading them.

September 2015

Click

here to return to the Index, U&S 31

The concept of “new social movements”

is based on the idea that movements such as feminism, anti-racist,

environmentalist, animal rights, anti-nuclear and peace movements – on

the rise since the 1970s – have broken from the “old” social movements based on the class struggle, primarily of the working class, and that they are an ontological “new” concept. They are inspired by post-structuralist and post-Marxist tendencies of the 1970s.

The concept of “new social movements”

is based on the idea that movements such as feminism, anti-racist,

environmentalist, animal rights, anti-nuclear and peace movements – on

the rise since the 1970s – have broken from the “old” social movements based on the class struggle, primarily of the working class, and that they are an ontological “new” concept. They are inspired by post-structuralist and post-Marxist tendencies of the 1970s.  However, in the rising democratic movements and rebellions around the

world, starting with the Arab uprisings in the autumn of 2011, this

tendency has not been strong enough. Despite their partial successes

and deep rooted changes, the fact that they were not able to finally

win is due to the structural weaknesses of these movements.

However, in the rising democratic movements and rebellions around the

world, starting with the Arab uprisings in the autumn of 2011, this

tendency has not been strong enough. Despite their partial successes

and deep rooted changes, the fact that they were not able to finally

win is due to the structural weaknesses of these movements.