In 1902 he gave precise instructions and a warning:

In 1902 he gave precise instructions and a warning:Italy

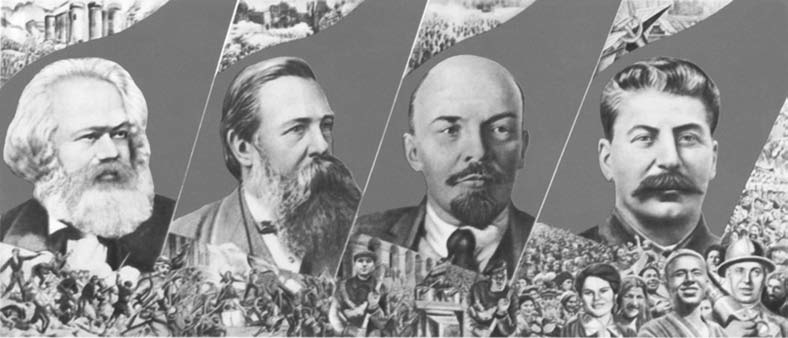

Communist Platform

Marx and Engels: the proletariat takes the leadership of the revolution in its hands

Marx and Engels formulated the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat in its main lines, beginning with the understanding of the historical and universal role of the working class, the most revolutionary class in society.

Marx in his early writings, evaluating the experience of the French Revolution, considered that for a "particular class" to be victorious in the revolution it should represent the broadest interests of society, becoming the "universal class," the "universal representative" of "society in general,” of the "whole of society":

"No class of civil society can play this role without arousing a moment of enthusiasm in itself and in the masses, a moment in which it fraternizes and merges with society in general, becomes confused with it and is perceived and acknowledged as its general representative, a moment in which its claims and rights are truly the claims and rights of society itself, a moment in which it is truly the social head and the social heart. Only in the name of the general rights of society can a particular class vindicate for itself general domination.... For the revolution of a nation, and the emancipation of a particular class of civil society to coincide, for one estate to be acknowledged as the estate of the whole society, all the defects of society must conversely be concentrated in another class, a particular estate must be the estate of the general stumbling-block, the incorporation of the general limitation, a particular social sphere must be recognized as the notorious crime of the whole of society, so that liberation from that sphere appears as general self-liberation." (K. Marx, Introduction to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, 1844).

From his early writings, Marx was clear that a revolution does not develop in a simplistic way, of "one class against another," but rather through a process in which one class leads all the other classes and subordinate elements of society, presenting itself as the bearer of universal interests and values.

This idea, which is the basis of the hegemonic role of the proletariat, Marx reaffirmed and clarified in subsequent writings, in which he recognized the existence of a "ruling class" and a group of "non-ruling classes," with their own interests, which can be represented by the proletariat.

Consequently, he stated in "The German Ideology"

"The class making a revolution appears from the very start, if only because it is opposed to a class, not as a class but as the representative of the whole of society; it appears as the whole mass of society confronting the one ruling class. It can do this because, to start with, its interest really is more connected with the common interest of all other non-ruling classes... Every new class, therefore, achieves its hegemony only on a broader basis than that of the class ruling previously, whereas the opposition of the non-ruling class against the new ruling class later develops all the more sharply and profoundly. Both these things determine the fact that the struggle to be waged against this new ruling class, in its turn, aims at a more decided and radical negation of the previous conditions of society than could all previous classes which sought to rule." (K. Marx, The German Ideology, Part I, Section B, under Ruling Class and Ruling Ideas.)

For Marx and Engels the proletariat is the class that brings together the revolutionary interests of society, because starting from its particular condition, and emancipating itself from the yoke of capitalism, it emancipates all humanity; since this class does not fight for the continued exploitation in other forms, but for the final elimination of the exploitation of man by man. In this role of the proletariat as the builder of the new communist society is the root and justification of the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat.

Based on these assumptions, defining the orientation of the vanguard of the proletariat, Marx and Engels wrote in the "Communist Manifesto":

"The Communists fight for the attainment of the immediate aims, for the enforcement of the momentary interests of the working class; but in the movement of the present, they also represent and take care of the future of that movement. ... the Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things." Clearly this does not mean tactical proposals, but strategic orientations.

During the revolution of 1848-49, Marx and Engels turned their efforts to preparing the working class to take up its hegemonic role, accelerating its class consciousness and creating its independent and revolutionary party.

In his mature works, Marx's speech is fully focused on the political, firmly anchored in historical materialism. The question of hegemony is linked to class analysis, the result of the "critique of political economy."

In "The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" (1852) Marx stressed the importance of the hegemony of the proletariat in its alliance with the peasants:

"The interests of the peasants, therefore, are no longer, as under Napoleon, in accord with, but in opposition to the interests of the bourgeoisie, to capital. Hence the peasants find their natural ally and leader in the urban proletariat, whose task is the overthrow of the bourgeois order."

The concept of hegemony also appears in the "Address of the General Counsel of the First International about the Paris Commune." Speaking of the Commune, Marx emphasized the leading role developed by the working class, which "took in its hands the leadership of the revolution."

In the Commune, the proletariat effectively and concretely exercised its hegemony over other allied social strata. As Marx explained, "this was the first revolution in which the working class was openly acknowledged as the only class capable of social initiative, even by the great bulk of the Paris middle class – shopkeepers, tradesmen, merchants – the wealthy capitalists alone excepted." (Marx, The Civil War in France).

Development and Importance of the Idea of Hegemony by Lenin

Marx and Engels developed the general idea of the hegemony of the proletariat. Lenin developed and expanded the concept of the hegemony of the proletariat under new historical conditions; he created a harmonious system of the leadership of the proletariat over the exploited masses of the city and countryside and gave precise answers to solve this problem in the period of the overthrow of tsarism and capitalism, as well as in the building of socialism.

Since the first years of the 20th century, Lenin raised the question of the hegemony and its tools, the political newspaper and the theoretical journal, linking it to the need to develop a broad political agitation in order to educate the proletariat and wrest the leadership of the political struggle from the hands of the liberals.

In 1902 he gave precise instructions and a warning:

In 1902 he gave precise instructions and a warning:

"It is our direct duty to concern ourselves with every liberal question, to determine our Social-Democratic attitude towards it, to help the proletariat to take an active part in its solution and to accomplish the solution in its own, proletarian way. Those who refrain from concerning themselves in this way (whatever their intentions) in actuality leave the liberals in command, place in their hands the political education of the workers, and concede the hegemony in the political struggle to elements which, in the final analysis, are leaders of bourgeois democracy." (Lenin, Political Agitation and the “Class Point of View," Collected Works, Vol. 5.)

Starting from the Third Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party (1905), Lenin developed the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat against the positions of the Mensheviks, who spoke against the leading, vanguard role of the proletariat in the democratic revolution (and therefore against the alliance with peasantry), and who called for the agreement with the democratic bourgeoisie, which, according to them, was the leading class.

In January of 1905 Lenin wrote in "Vperyod": "It is this support of all the inconsistent (i.e., bourgeois) democrats by the only really consistent democrat (i.e., the proletariat) that makes the idea of hegemony a reality. ... From the proletarian point of view hegemony in a war goes to him who fights most energetically, who never misses a chance to strike a blow at the enemy, who always suits the action to the word, who is therefore the ideological leader of the democratic forces, who criticizes half-way policies of every kind." (Lenin, Working-Class and Bourgeois Democracy, Collected Works, Vol. 8.)

According to these writings, it is clear that, in Lenin’s thinking, hegemony depends on the revolutionary initiative of the working class, on the ability of the masses for leadership and political unification, on its full consciousness of its revolutionary objectives and on the example that the communists have to offer. Through this many-sided activity, the Party exercises its fundamental hegemonic role.

With this, hegemony acquires a broader sense of political and practical leadership, because it implies example and moral superiority, the emergence of new states of mind in the working class, which is achieved through struggle on the ideological front.

The work "Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution" is fundamental to understanding the Leninist development of this concept. In it, Lenin, starting from his analysis of the Russian situation and a new conception of the relationship between bourgeois revolution and proletarian revolution, presented new tactical principles for developing a policy of alliance with the mass of the peasantry and a policy of isolation of the liberal bourgeoisie, in order to carry out the decisive victory over tsarism.

In the preface to this text, written in July of 1905, Lenin raised the fundamental question: "The outcome of the revolution depends on whether the working class will play the part of a subsidiary to the bourgeoisie, a subsidiary that is powerful in the force of its onslaught against the autocracy but impotent politically, or whether it will play the part of leader of the people's revolution. " (Lenin, Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, Collected Works, Vol. 9).

Against the objections of the Mensheviks, Lenin clarified the tasks and policies of the proletariat, on the question of the hegemonic class:

"The proletariat must carry to completion the democratic revolution, by allying to itself the mass of the peasantry in order to crush by force the resistance of the autocracy and to paralyze the instability of the bourgeoisie. The proletariat must accomplish the socialist revolution, by allying to itself the mass of the semi-proletarian elements of the population in order to crush by force the resistance of the bourgeoisie and to paralyze the instability of the peasantry and the petty bourgeoisie." (Ibid.)

Therefore, the proletariat should not marginalize itself from the bourgeois revolution; it should not be indifferent to it and leave the leadership of the struggle to a weak and inconsistent bourgeoisie. On the contrary, it had to place itself vigorously and consistently at the head of the whole people, of all the laborers, in order to carry the revolution through to its end.

In 1907, addressing the fundamental disagreements between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks on the driving force of the Russian revolution and on the tactics to be followed, Lenin insisted:

"The essence of the dispute between the two wings of the Russian Social-Democratic Party is in deciding whether to recognize the hegemony of the liberals or whether to strive for the hegemony of the working class in the bourgeois revolution. " (Lenin, The Elections to the Duma and the Tactics of the Russian Social-Democrats, Collected Works, Vol. 12).

Under Lenin’s leadership, one of the distinctive features of Bolshevism became the acceptance of the principle of the hegemony of the proletariat over the petty bourgeoisie. Without the hegemony of the proletariat the revolution would end in nothing.

In 1911 Lenin, polemicizing with the Menshevik liquidators, firmly upheld the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat and its implementation as an indispensable condition for the transformation of the proletariat into the leading class of the revolution. In a scathing article he wrote:

"From the standpoint of Marxism the class, so long as it renounces the idea of hegemony or fails to appreciate it, is not a class, or not yet a class, but a guild, or the sum total of various guilds.... Marxists are in duty bound – despite all and sundry renunciators – to uphold its idea in the present and in the future" (Lenin, Marxism and "Nasha Zarya," Collected Works, Vol. 17).

Soon after, in the journal "Mysl," Lenin explained what hegemony consists of and emphasized the connection between the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat and the question of liquidationism:

"The hegemony of the working class is the political influence which that class (and its representatives) exercises upon other sections of the population by helping them to purge their democracy (where there is democracy) of undemocratic admixtures, by criticizing the narrowness and short-sightedness of all bourgeois democracy, by carrying on the struggle against ‘Cadetism’ (meaning the corrupting ideological content of the speeches and policy of the liberals), etc., etc." (Lenin, Those Who Would Liquidate Us, Collected Works, Vol. 17).

It is important to note that for Lenin the exercise of hegemony was not limited to the role played by the vanguard detachment of the working class, but that it corresponds to the entire mass of the working class, its organizations and its various sectors.

For Lenin, the hegemony of the proletariat is indivisible and has a head, the Party, a body, the class, and extends over the other strata of the population interested in the revolution, especially the peasantry.

To clarify and specify the line of the party and the tasks of the proletariat, Lenin again took up positions against the Mensheviks, Trotsky and others who believed that the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat in the revolution and in the transition to socialism was obsolete:

"The proletariat, as the only consistently revolutionary class of contemporary society, must be the leader in the struggle of the whole people for a fully democratic revolution, in the struggle of all the working and exploited people against the oppressors and exploiters. The proletariat is revolutionary only insofar as it is conscious of and gives effect to this idea of the hegemony of the proletariat.... The proletarian who is not conscious of the idea that his class must be the leader, or who renounces this idea, is a slave who does not realize his position as a slave; at best he is a slave who fights to improve his condition as a slave, but not one who fights to overthrow slavery."

Therefore, "To preach to the workers that what they need is ‘not hegemony, but a class party’ means to betray the cause of the proletariat to the liberals; it means preaching that Social-Democratic labor policy should be replaced by a liberal labor policy. Renunciation of the idea of hegemony, however, is the crudest form of reformism in the Russian Social-Democratic movement” (Lenin, Reformism in the Russian Social-Democratic Movement, Collected Works, Vol. 17).

Undoubtedly, for Lenin the hegemony of the proletariat – that is, its role as guide, as leader of the popular masses and of the democratic movement – constitutes one of the fundamental principles of Marxism. Its negation or renunciation is synonymous with opportunism, with reducing the proletariat to one class in bourgeois society, instead of being the vanguard of all oppressed and exploited in the social revolution.

If the Party of the proletariat does not take up the idea of the hegemony of the class, it will not be a truly independent and revolutionary party, but a vulgar reformist or liberal party, as Lenin stated.

The hegemony of the proletariat, established by Lenin, was opposed to the point of view of the opportunists who did not believe in the maturity of the conditions for the revolution and waited inactively for the proletariat to become the majority in society. Lenin’s idea of hegemony is the negation of mechanical determinism and of the static and tailist positions that considered that the leading role of the proletariat in the phase of the bourgeois-democratic revolution was unthinkable.

Based on the experience acquired in Russia and on the analysis of imperialism, Lenin clarified the nature of revolutions in our era, deepening the concept of hegemony and closely linking it to the struggle for the revolutionary seizure of state power.

In July of 1916, pointing out that the social revolution of the proletariat is inconceivable without the uprising of the oppressed social strata and nationalities, he wrote:

"The

socialist revolution in Europe cannot be anything other than an

outburst of mass struggle on the part of all and sundry oppressed and

discontented elements. Inevitably, sections of the petty bourgeoisie

and of the backward workers will participate in it – without such

participation, mass struggle is impossible, without it no revolution is

possible – and just as inevitably will they bring into the movement

their prejudices, their reactionary fantasies, their weaknesses and

errors. But objectively they will attack capital, and the

class-conscious vanguard of the revolution, the advanced proletariat,

expressing this objective truth of a variegated and discordant, motley

and outwardly fragmented, mass struggle, will be able to unite and

direct it, capture power" (Lenin, The Discussion of Self-Determination Summed Up, Collected Works, Vol. 22).

"The

socialist revolution in Europe cannot be anything other than an

outburst of mass struggle on the part of all and sundry oppressed and

discontented elements. Inevitably, sections of the petty bourgeoisie

and of the backward workers will participate in it – without such

participation, mass struggle is impossible, without it no revolution is

possible – and just as inevitably will they bring into the movement

their prejudices, their reactionary fantasies, their weaknesses and

errors. But objectively they will attack capital, and the

class-conscious vanguard of the revolution, the advanced proletariat,

expressing this objective truth of a variegated and discordant, motley

and outwardly fragmented, mass struggle, will be able to unite and

direct it, capture power" (Lenin, The Discussion of Self-Determination Summed Up, Collected Works, Vol. 22).

Here is a splendid illustration of the hegemonic role of the proletariat!

After the October Socialist Revolution, Lenin closely linked the concept of hegemony to the practical construction of the dictatorship of the proletariat, indispensable for the transition to a classless society.

We have an example of this in his speech of December of 1921, in which Lenin addresses the problem of the role of the trade unions under socialism:

"On the one hand, the trade unions, which take in all industrial workers, are an organization of the ruling, dominant, governing class, which has now set up a dictatorship and is exercising coercion through the state.... On the other hand, the trade unions are a ‘reservoir’ of the state power. This is what the trade unions are in the period of transition from capitalism to communism. In general, this transition cannot be achieved without the leadership of that class which is the only class capitalism has trained for large-scale production and which alone is divorced from the interests of the petty proprietor." (Lenin, The Trade Unions, The Present Situation and Trotsky’s Mistakes, Collected Works, Vol. 32).

Here, Lenin focuses on a fundamental aspect of the new system of power, which lives in the dialectic of the two functions exercised by the proletariat through its organs and apparatus: coercion (principally by the state), and educational, consensual (in the specific role played by the unions, which as Lenin said are "between the Party and the government").

The hegemony of the proletariat, its force of consolidation and expansion, is here conceived of as a vital step towards communism and is inseparable from the dictatorship of the proletariat. The latter, however, is exercised directly, not by the unions, due to their nature, but by the Soviets and above all by the Communist Party, an essential factor in the theoretical and practical leadership within the class of proletarians and among the organizations of this same class.

As we have seen, hegemony to Lenin is a strategic concept, which was implemented in practice in the revolution of 1905, in the revolution of February of 1917, in the October Socialist Revolution and in the building of socialism.

Stalin: the Hegemony of the Proletariat Is a Living Fact

Stalin recognized the Leninist thesis of the hegemony of the proletariat as a fundamental question in the era of the proletarian revolution and already used this concept in his early writings.

In a pamphlet published in 1906, he directed his polemic against the positions of the Mensheviks who, in the words of Martinov, considered that the hegemony of the proletariat in the revolution was a "dangerous utopia."

Stalin very clearly confirmed the position of the Bolsheviks:

"Whoever champions the interests of the proletariat, whoever does not want the proletariat to become a hanger-on of the bourgeoisie, pulling the chestnuts out of the fire for it, whoever is fighting to convert the proletariat into an independent force and wants it to utilize the present revolution for its own purpose – must openly condemn the hegemony of the bourgeois democrats, must strengthen the ground for the hegemony of the socialist proletariat in the present revolution." (Stalin, The Present Situation and the Unity Congress of the Workers' Party, Works, Vol. I).

In the last lines of the pamphlet he raises the fundamental dilemma to the comrades:

"Should the class-conscious proletariat be the leader in the present revolution, or should it drag at the tail of the bourgeois democrats? We have seen that the settlement of this question one way or another will determine the settlement of all the other questions." (Ibid.)

In other writings of the same period Stalin developed a relentless political and ideological struggle on the need for an alliance with the peasantry and the hegemony of the proletariat in this alliance, in order to systematically prepare, insure and reinforce it.

This is an essential problem of strategy, a decisive condition that determines the solution of the fundamental question of the revolution: the question of political power.

For Stalin: "The hegemony of the proletariat is not a utopia, it is a living fact; the proletariat is actually uniting the discontented elements around itself. And whoever advises it ‘to follow the bourgeois opposition’ is depriving it of independence, is converting the Russian proletariat into a tool of the bourgeoisie" (Stalin, Preface to the Georgian Edition of K. Kautsky's Pamphlet “The Driving Forces and Prospects of the Russian Revolution," Works, Vol. 2).

The revolution of February 1917 and even more Red October clearly prove this "real fact" that ensured the triumph of the most revolutionary class in society.

It is important to keep in mind that in the text "Concerning The Question of the Strategy and Tactics of the Russian Communists" (1923), as in "The Foundations of Leninism" (1924), Stalin insisted on a key point of Bolshevik strategy:

Hence the need for the proletariat to exercise and maintain its hegemony over the mass of the peasantry in the area of the building of socialism in general, and of industrialization in particular.

Stalin emphasized this role repeatedly, clarifying that force alone is not enough to win: "While being the shock force of the revolution, the Russian proletariat at the same time strove for hegemony, for political leadership of all the exploited masses of town and country, rallying them around itself, wresting them from the bourgeoisie and politically isolating the bourgeoisie. " (Stalin, Interview with the First American Labor Delegation, September 9, 1927, Works, Vol. X).

This position was always defended by Stalin against Trotskyism, a current opposed to Leninism, which does not understand nor recognize the idea of the hegemony of the proletariat.

As a leader of the international communist movement, Stalin raised the question of the hegemony of the proletariat in the liberation movements of the countries oppressed by imperialism and in the colonies, in all the popular revolutions. Thus he contributed to spreading the concept in China and India, that is, globally.

The idea of the hegemony of the proletariat in the revolutionary

struggle is a fundamental question, which is why our teachers have

always struggled in order to turn it from an aspiration into a reality.

In particular Lenin and Stalin raised the open battle against the

currents and trends that did not understand or that rejected the

hegemony of the proletariat, and the principal instrument for

establishing it in the era of proletarian revolution: a communist party

that is fully independent ideologically, politically and

organizationally as an indispensable condition to exercise the hegemony

of the proletariat, both in the struggle to overthrow capitalism and in

the building of socialism and communism.

June of 2015

Click here to return to the Index, U&S 31