Turkey

Revolutionary Communist Party of Turkey (TDKP)

The June Resistance in Turkey

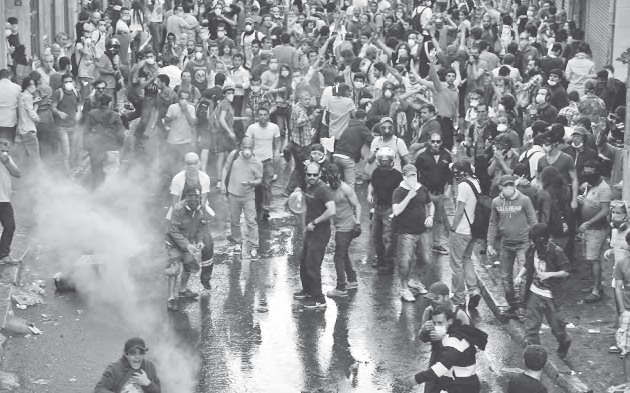

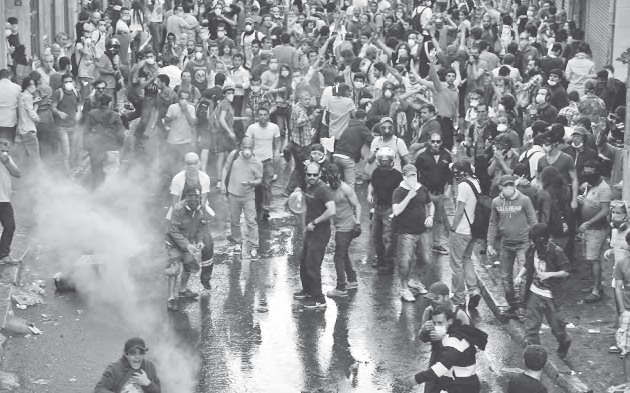

In Turkey, what has become known as the June Resistance is a series of

events which have already left their mark on history. These events were

sparked by a four-day sit-in of a group of environmentalists at Gezi

Park, angry at the government’s plans to redevelop that part of Taksim

Square. On 31 May 2013 police attacked fiercely to disperse the

protestors. When this was broadcast on TV, people began to pour into

the square in their thousands.

In the following days, demonstrations spread into other neighbourhoods

in Istanbul, then to 79 of the 81 cities in Turkey, turning into a

popular resistance. More than 4 million people have taken part in these

protests in various forms. Police fiercely attacked all kinds of

actions, from street demonstrations to turning off the lights in ones

home and making noise with pots and pans. Five people have died as a

result of police attacks. More than 7 thousand people have been

injured, while a dozen have lost their sight because of tear gas

canisters. Hundreds of people have been arrested.

Demonstrations which began over environmentalist concerns have turned

into huge protests demanding the resignation of the government,

spreading into other parts of the country and continuing in June

despite police terror. The government had to take a step back and

announced that they would recognize the judicial rulings regarding the

fate of the redevelopment plan for Gezi Park.

It seems that for the time being the mass movement has retreated. The

events have taken the form of “park forums” in the big cities such as

Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir, where discussions are held to answer the

question of how to carry on the struggle.

As soon as the mass movement started, the party of the working class

and the revolutionary organisations played an important part in

intervening, helping and contributing to the organisation of the mass

demonstrations and street clashes, both during and after the Taksim

Square and Gezi Park protests. However, this did not change the

spontaneous character of this popular movement, nor did the slogan

demanding the “resignation of the government”.

The fact that this movement was brought about by various sections of

various classes, thus not developing as a struggle for political power,

and that the resistance developed, in appearance, against the

repressive measures of the government which “interfered in the

lifestyle of the society”, should not conceal profound economic, social

and political reasons behind these protests.

The AKP came to govern as a result of the wish for change

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been in the government for

the past 11 years and has received a serious “impact” as a result of

these events. This party increased its vote in each election and

received 50% of the votes in the last one in 2011. The popular support

they get is due to the fact that this party uses the people’s desire

for change skilfully.

Turkey was engulfed in a profound economic crisis in 2001. In the

elections in 2002 the people of Turkey were disillusioned with the then

existing bourgeois political parties, and with its promise for “social

welfare” and “advanced democracy” the newly established AKP came out of

the elections with a majority of the votes. As it were, the AKP adopted

the motto “Down with the old order!” and began to put the blame for all

ills on the Republican People’s Party (CHP), now the main opposition

party, and on the one-party rule which this party had established

following the Independence War.

The AKP is a split from the Welfare Party of the Islamist “national

vision” tradition. It has received unlimited support from the US and

the EU, which have seen this party as an instrument to make Turkey a

“model country” of “moderate Islam” in accordance with the Greater

Middle East Project of US imperialism.

Also the AKP was the most appropriate instrument for a smooth

realisation of neoliberal transformation. As a result of the AKP’s

economic policies, in the form of privatisation, real estate purchases

and portfolio investments, scores of international capital and finance

companies have flooded the country, which had been fighting against the

destruction caused by the 2001 crisis. While in 22 years from 1980 to

2002 foreign investment into Turkey was a mere $35 billion dollars,

this increased more than 10-fold in the period 2003-2012 to a huge $400

billion dollars.

In the short term the influx of “hot money” has made the economy

fragile. Turkey is now the hunting ground for the stock and currency

exchange market speculators.

Neoliberal transformation, increasing poverty

Neoliberal transformation, which began with the Turgut Ozal government

in the mid- 1980s following the military coup, has become widespread

with the AKP government. Most national obstacles have been lifted for

international capital to enter into the country and invest in any areas

they wanted. Privatization in the first 5 years of the AKP government

surpassed that of the previous 25 years. New legislation meant casual

work, increased unemployment and less powerful trade unions. Official

figures put unemployment at 9%, while the actual percentage is close to

17%, with 25% amongst the youth. Education and health have been opened

to market rules and social security institutions have been gathered

under one roof with a much narrower scope. The poor masses of people

deprived of all forms of social security have been made dependent on

the AKP through food and fuel aid. The AKP government has brought about

“redevelopment projects” in the cities, from which the city poor are

forcefully relocated out of the town centres, in order to open up new

rentier arenas for international and collaborationist capital.

Neoliberal transformation, which began with the Turgut Ozal government

in the mid- 1980s following the military coup, has become widespread

with the AKP government. Most national obstacles have been lifted for

international capital to enter into the country and invest in any areas

they wanted. Privatization in the first 5 years of the AKP government

surpassed that of the previous 25 years. New legislation meant casual

work, increased unemployment and less powerful trade unions. Official

figures put unemployment at 9%, while the actual percentage is close to

17%, with 25% amongst the youth. Education and health have been opened

to market rules and social security institutions have been gathered

under one roof with a much narrower scope. The poor masses of people

deprived of all forms of social security have been made dependent on

the AKP through food and fuel aid. The AKP government has brought about

“redevelopment projects” in the cities, from which the city poor are

forcefully relocated out of the town centres, in order to open up new

rentier arenas for international and collaborationist capital.

A few official statistics will show the extent of impoverishment during

the AKP rule. In Turkey, nearly 11.454 million people live on less than

326 Turkish Lira (1 dollar=2 TL) per month. Last year this figure was

10.401 million. In other words, nearly 1.053 million people joined the

ranks of the poor. The severity of this problem becomes clearer as the

hunger threshold is set at 1020 TL and the poverty line at 3222 TL per

month.

In January 2013, the number of households with monthly income of less

than 326 TL was 2.518 million, which rose to 2.752 million in April, an

increase of 234 thousand.

The number of people who had consumer debts on credit cards was 2.4

million in 2003, and 13.2 million in 2012. Total credit card

indebtedness of households stood at 6.5 billion TL in 2002, shooting up

to 264.3 billion TL in 2012. In short, instead of its promises of social prosperity the

11 years of AKP government has brought poverty and unemployment to the

working people of Turkey.

AKP’s “advanced democracy”

Another promise of the AKP was in the arena of democracy and liberties.

The fact that some laws and regulations initiated by the AKP as part of

the EU harmonization process received the approval of the bourgeois and

left liberal circles and were presented with a show in the media has

created certain illusions among the masses and been used by this party

as a propaganda instrument claiming that: “Step by step we are moving

towards advanced democracy”.

Moreover, in its second term the AKP said that it would wipe out the

so-called “deep state” and put an end to military tutelage. With this

mindset, many people have been arrested, including high ranking

military officials. The intellectuals who were hopeful of democrati-

sation supported the AKP. Bureaucracy and the judiciary have been

restructured. By eradicating the old, AKP established its own “deep

state”, with the military and judiciary under government control. Last

but not least was the proposal for a presidential administration.

When the veil on those promises was lifted and people realised how

futile the democrati- sation pledge was, the AKP began to lose support.

Those liberal circles that supported the AKP referendum to change the

constitution were now gradually distancing themselves from the government.

During the first days of the AKP government, in response to the

accusations that the AKP had a hidden agenda and wanted to bring about

Sharia, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Er- dogan tried to reassure people

that there would not be any interference in anyone’s lifestyle or

religious beliefs. However, since his third term, as he calls his

“mastery period”, his practise cost him the support of the secular

middle and lower classes.

He began to shape social political life in accordance with his own

ideological and religious belief systems. Both with his rhetoric and in

practice Erdogan insulted women. For example, he tried to ban abortion.

He suggested that women should stay home and have three children.

Instead of preventing rape and making deterring regulations, rapes

increased 1400% during his administration. Through new regulations in

education he opened the path for an early marriage for girls and early

employment for boys. He has given a religious and conservative

character to the national curriculum. He banned the sale of alcohol

after 10 pm as well as sitting outside in bars.

He increased repression in the universities. He made possible social

control by conservatism through neighbourhood organisations and

self-appointed informants and interventionists through whom it became

legitimate to interfere in people’s lives who were thought not to be in

accordance with the conservative/religious rules.

The Prime Minister himself divided the people into two: religious

people and secular ones, the latter being denounced as degenerate.

Through continuous incitement of his electors he tried to intimidate

the other camp. Confident of the support of his 50% of the electors,

Erdogan thought that the other half of the population was so polarised

that they could not unite in action. Also the fact that there had not

been much mass reaction against the AKP attacks made it easy for him to

blame every section who resisted him as marginal people, vandals or

terrorists. He not only blamed them but also had them tear gassed. In

short, the AKP government recklessly tickled the nerves of society.

The immediate questions waiting for a solution have been the Kurdish

question and secularism. Religion has been under state control, serving

the majority Sunni sect and discriminating against the 15 million

strong Alevis. During AKP rule discrimination against and isolation of

Alevis has increased. Kurds, Alevis and other people of a different

ethnicity or religious sect have never been free in Turkey.

The Kurdish question

The AKP government, like the ones before it, at first tried to “solve”

the Kurdish Issue by military means. The Kurdish regions were

surrounded by the military and the police presence and operations were

heightened. Thousands of Kurdish politicians, trade unionists, lawyers

and intellectuals were prosecuted. But all this was not enough to break

the resistance of the Kurdish people. This aggression not only helped

reveal that the AKP was wearing a “democrat” mask; it also helped erode

their support among Kurds. The never- ending military funerals were the

cause of increased questioning by the public of the AKP government’s

line on the Kurdish Issue, and increasing criticism of the AKP.

Coupled with changes in the international situation, and being unable

to cope with the pressure, in early 2013 the AKP government announced

the start of negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan – the imprisoned leader

of the PKK, which has been in armed conflict with the state for 30

years. Despite the fact that it has been months since the start of

negotiations, since weapons have been silenced and the Kurdish military

personnel withdrew beyond the Turkish borders, the government has not

taken a single step towards democracy, national equality or freedom.

This makes their sincerity for a resolution questionable and the fear

of a return to military conflict is continues.1

Coupled with changes in the international situation, and being unable

to cope with the pressure, in early 2013 the AKP government announced

the start of negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan – the imprisoned leader

of the PKK, which has been in armed conflict with the state for 30

years. Despite the fact that it has been months since the start of

negotiations, since weapons have been silenced and the Kurdish military

personnel withdrew beyond the Turkish borders, the government has not

taken a single step towards democracy, national equality or freedom.

This makes their sincerity for a resolution questionable and the fear

of a return to military conflict is continues.1

Turkey’s cooperation with the chiefs of the Free Syrian Army and the

Nusra Front, which admits to having links with Al-Qaida, in order to

prevent the Kurds acquiring a status in Ro- java (Syrian Kurdistan), is

the litmus test of the AKP’s real intentions on the Kurdish issue and

diminishes trust in the government. Turkey, through its political

stance, has taken a side in the Syrian conflict. The AKP government has

been warmongering in the Syrian conflict and not only has it allowed

terrorist groups to use its territory as a base but it has also

provided them with training and arms and supported a series of

provocations.

It has defined a number of roles for itself, ranging from taking a role

in the redistribution of natural energy resources in the region to

being a model country for the region and a political broker in

negotiations. Despite the falling out and cooling of relationships

after the military coup in Egypt regarding the reaction and political

line to be followed, trade and political relations with a number of

reactionary, anti-Syrian Islamic states in the region have been

developed. These steps have made Turkey an open target for terrorist

attacks. Finally the bombing in Reyhanli has caused scores of deaths.

The financial, social and political developments prior to the June Resistance can be summarised as such.

Days of resistance

The June Resistance was the explosive reaction to the developments

summarised above. Those who joined the protests demanded freedom,

democracy and humane treatment. The resistance has become the

questioning, criticism and rejection of the whole period of the AKP

rule.

Those who started the resistance really were people with environmental

concerns but the police brutality that ensued popularised it. A great

majority of those who were in the resistance from beginning to end were

the youngest. But those who kept arriving in Tak- sim from all over the

city were not just the youth. People of all ages, cultures and

convictions joined in. It was initially university students from

nearby, their young lecturers and blue collar service sector workers

but later they were joined by the unemployed, workers, women and people

from all working sectors.

The majority of the youth were not affiliated with any party and most

stated that they were apolitical. Besides those, radical left

organisations, nationalist-pro-state organisations, revolutionary

Islamists and LGBT individuals were among the mass ranks. Trade

associations have also taken part. The main opposition party’s youth

associations and MPs were also on the streets. The umbrella

organisation of this union, Taksim Solidarity Platform, was made up of

135 groups of varying sizes.

The most important fact was that groups unlikely to be together were

united in solidarity. The biggest workers’ and public sector unions’

confederations, due to the dominance of the trade union bureaucracy in

their management, have kept their distance from the resistance but

workers always took part. The Public Sector Workers’ Unions

Confederation (KESK) has brought forward its pre-planned action to

support the resistance. The Revolutionary Workers’ Unions Confederation

(DISK) made a statement supporting the resistance and called for

participation in the demonstrations. Airline workers have unified their

strikes with the resistance.

Attempts to divide the resistance

From the start the government tried to smear the resistance, trying to

show it as a conspiracy by “external forces” intent on damaging

Turkey’s diplomatic prowess or by the “interest lobby”(!). The AKP

leadership, trying to take advantage of the Kurdish movement’s

hesitation (due to the presence of the nationalist left) to join the

resistance in the early days, labelled the resistance a provocation

against the Kurdish peace process, in an attempt to muddy the waters

and divide the resistance. The government did not refrain from accusing

the resistance of violent acts towards Muslim women with head scarves

and drinking alcohol in a mosque that was used as a makeshift

infirmary, even though these allegations have never been proven.

However, the government’s attempts to divide the movement backfired.

The Kurdish national movement has supported the resistance; even though

they were not in the leadership, they were represented in

demonstrations and have taken part in platforms. In Gezi Park itself,

conflicts between Kurds and those influenced by chauvinism were limited

to small skirmishes and quickly quelled. Insurgents carrying Turkish

and BDP (legal Kurdish Party) flags have resisted police brutality

hand-in-hand. While the “anti-capitalist Muslims” were praying in Gezi

Park, secular and atheist youth were guarding them (those with an

Islamic outlook akin to anti-capitalist Muslims have taken part in

demonstrations particularly in working class areas). Women that live

and dress according to Islamic values have made statements exposing the

government’s attempts to use religious lies. This has helped defeat the

government’s religious provocations.

The more the government tried to divide the resistance, the more the

masses saw the need to unite for democracy, through their practical

struggle and actions. They have realised that real democracy cannot be

achieved without a resolution of the Kurdish Issue. Thus nationalist

attempts to draw the struggle along their own course were defeated from

the start. The murder of a Kurdish youth by the military in a protest

against the planned building of a border post in the Lice district of

Diyarbakir was condemned with the slogans of “Gezi and Lice

hand-in-hand” and “Lice is Gezi” by tens of thousands of people.

It has become clearer in the eyes of the Turkish workers that the ones

who killed the four protesters in police attacks and those who killed

the Kurdish youth are the same; in other words, those who deny Kurdish

rights and those who stand in the way of democratic demands are the

same regressive groups. Furthermore, the majority of what has happened

during the June Resistance has developed the opportunities for a

democratic popular solution to the Kurdish issue.

Public self-confidence has risen

Bourgeois liberal circles and the liberal left have particularly tried

to hide the fact that the movement has shaken the government and has

the potential to target the system. Using the spontaneity of the

movement they indulged in “making a fetish of the unorganised

movement”. Ignoring the demands and actions of millions, they tried to

put the focus on the individual; they praised “the actions of an

unorganised individual”. However the spontaneity of the mass movement,

which started on 31st May and is still continuing today with Park

Forums, does not imply a totally unorganised course for the movement.

Therefore, with the support of revolutionary parties and organisations,

the masses have organised in different ways within their activities.

The organisation of demonstrations involving hundreds of thousands in

an orderly manner is a good indicator of the ability of the masses to

organise in action. Besides, the fact that organisation is the main

topic of discussion in Park Forums shows that the resisting masses

realise, through experience, the need for organised struggle.

The biggest gain of the June Resistance is the realisation by the

masses that when united, even “the most powerful” governments that seem

untouchable can be defeated. From this perspective the public has

gained great selfconfidence. The public reaction to any social issue,

no matter how small, since the resistance (usually accompanied by the

slogan “Taksim is everywhere, everywhere is resistance”) is a result of

this self-confidence.

As pointed out above, the Resistance did not develop as a power

struggle. Hence the slogan “the government should resign” has served as

an agitation, an expression of public anger at an oppressive government

that intervenes in people’s lives. Furthermore, the AKP government has

received a “sword wound” from the resistance, which marks the beginning

of the end for them. The AKP government, which gathered support with

promises of change has, in the face millions demanding change for

democracy and freedom, suddenly showed itself to be the most regressive

force in the country. The illusion of the “Party of change” has ended.

This stark reality also helped the cracks in the AKP to surface. This

is why Prime Minister Erdogan held staged, Nazi-like rallies, first to

repair the cracks within his party, and secondly to address the impasse

in “legitimacy” he found himself in when faced with the strength of the

masses.

What next?

We can say that the future is bleak for Er- dogan and his AKP.

Universities are starting a new season in September and the AKP

government, worried about new mass protests led by the university

students, was already feeling a “September syndrome” in the summer

months. The football season has started and groups of fans are already

chanting “Everywhere is Taksim, resistance is everywhere”.

The government has passed unprecedented laws against the uprising but

they seem to have had no effect so far. Local elections will be held in

March 2014 and this could be the hardest test so far in the history of

the AKP. The local elections are one of the main topics discussed in

Park Forums. Efforts to mould and shape the democratic gains of the

June Resistance to join up with the workers’ and democratic forces in

local elections are already under way. The slogan used in the toughest

struggles of the June Resistance was “this is the start, the struggle

will continue”. When the deep social, political and economic problems

of the country are considered, the struggle will surely continue... and

this time with the gains and lessons of the June Resistance behind it.

September 2013

Note:

1) Since this article was written, the Kurdistan Communities Union

(KCK), a Kurdish umbrella organisation which consists of both political

and armed groups within the Kurdish movement, including the PKK,

announced that they had stopped the withdrawal of their armed forces

beyond Turkey's borders due to the government not keeping their promise

to take steps towards democratisation.

Click here to return to the Index, U&S 27

Neoliberal transformation, which began with the Turgut Ozal government

in the mid- 1980s following the military coup, has become widespread

with the AKP government. Most national obstacles have been lifted for

international capital to enter into the country and invest in any areas

they wanted. Privatization in the first 5 years of the AKP government

surpassed that of the previous 25 years. New legislation meant casual

work, increased unemployment and less powerful trade unions. Official

figures put unemployment at 9%, while the actual percentage is close to

17%, with 25% amongst the youth. Education and health have been opened

to market rules and social security institutions have been gathered

under one roof with a much narrower scope. The poor masses of people

deprived of all forms of social security have been made dependent on

the AKP through food and fuel aid. The AKP government has brought about

“redevelopment projects” in the cities, from which the city poor are

forcefully relocated out of the town centres, in order to open up new

rentier arenas for international and collaborationist capital.

Neoliberal transformation, which began with the Turgut Ozal government

in the mid- 1980s following the military coup, has become widespread

with the AKP government. Most national obstacles have been lifted for

international capital to enter into the country and invest in any areas

they wanted. Privatization in the first 5 years of the AKP government

surpassed that of the previous 25 years. New legislation meant casual

work, increased unemployment and less powerful trade unions. Official

figures put unemployment at 9%, while the actual percentage is close to

17%, with 25% amongst the youth. Education and health have been opened

to market rules and social security institutions have been gathered

under one roof with a much narrower scope. The poor masses of people

deprived of all forms of social security have been made dependent on

the AKP through food and fuel aid. The AKP government has brought about

“redevelopment projects” in the cities, from which the city poor are

forcefully relocated out of the town centres, in order to open up new

rentier arenas for international and collaborationist capital. Coupled with changes in the international situation, and being unable

to cope with the pressure, in early 2013 the AKP government announced

the start of negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan – the imprisoned leader

of the PKK, which has been in armed conflict with the state for 30

years. Despite the fact that it has been months since the start of

negotiations, since weapons have been silenced and the Kurdish military

personnel withdrew beyond the Turkish borders, the government has not

taken a single step towards democracy, national equality or freedom.

This makes their sincerity for a resolution questionable and the fear

of a return to military conflict is continues.

Coupled with changes in the international situation, and being unable

to cope with the pressure, in early 2013 the AKP government announced

the start of negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan – the imprisoned leader

of the PKK, which has been in armed conflict with the state for 30

years. Despite the fact that it has been months since the start of

negotiations, since weapons have been silenced and the Kurdish military

personnel withdrew beyond the Turkish borders, the government has not

taken a single step towards democracy, national equality or freedom.

This makes their sincerity for a resolution questionable and the fear

of a return to military conflict is continues.